| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

04Jun13

Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

A/HRC/23/58

Distr.: General

4 June 2013

Original: EnglishHuman Rights Council

Twenty-third session

Agenda item 4

Human rights situations that require the Council's attentionReport of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic |*|

Summary

The conflict in Syria has reached new levels of brutality. This report documents for the first time the systematic imposition of sieges, the use of chemical agents and forcible displacement. War crimes, crimes against humanity and gross human rights violations continue apace. Referral to justice remains paramount.

This report covers the period 15 January to 15 May 2013. The findings are based on 430 interviews and other collected evidence.

Government forces and affiliated militia have committed murder, torture, rape, forcible displacement, enforced disappearance and other inhumane acts. Many of these crimes were perpetrated as part of widespread or systematic attacks against civilian populations and constitute crimes against humanity. War crimes and gross violations of international human rights law - including summary execution, arbitrary arrest and detention, unlawful attack, attacking protected objects, and pillaging and destruction of property - have also been committed. The tragedy of Syria's 4.25 million internally displaced persons is compounded by recent incidents of IDPs being targeted and forcibly displaced.

Anti-Government armed groups have also committed war crimes, including murder, sentencing and execution without due process, torture, hostage-taking and pillage. They continue to endanger the civilian population by positioning military objectives in civilian areas. The violations and abuses committed by anti-Government armed groups did not, however, reach the intensity and scale of those committed by Government forces and affiliated militia.

There are reasonable grounds to believe that chemical agents have been used as weapons. The precise agents, delivery systems or perpetrators could not be identified.

The parties to the conflict are using dangerous rhetoric that enflames sectarian tensions and risks inciting mass, indiscriminate violence, particularly against vulnerable communities.

War crimes and crimes against humanity have become a daily reality in Syria where the harrowing accounts of victims have seared themselves on our conscience.

There is a human cost to the increased availability of weapons. Transfers of arms heighten the risk of violations, leading to more civilian deaths and injuries.

A diplomatic surge is the only path to a political settlement. Negotiations must be inclusive, and must represent all facets of Syria's cultural mosaic.

Contents

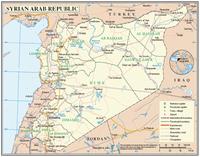

Paragraphs I. Introduction 1-37 A. Challenges 4-5 B Methodology 6-9 II. Context 10-37 A. Political context 10-17 B. Military context 18-31 C. Socio-economic and humanitarian context 32-37 III. Violations concerning the treatment of civilians and hors de combat fighters 38-102 A. Massacres 38-50 B. Other unlawful killing 51-63 C. Arbitrary arrest and detention 64-69 D. Hostage taking 70-77 E. Enforced disappearance 78-81 F. Torture and other forms of ill-treatment 82-90 G. Sexual violence 91-95 H. Violations of children's rights 96-102 IV. Violations concerning the conduct of hostilities 103-151 A. Unlawful attacks 103-114 B. Specifically protected persons and objects 115-126 C. Pillaging and destruction of property 127-135 D. Illegal Weapons 136-140 E. Sieges 141-148 F. Forced Displacement 149-151 V. Accountability 152-156 VI. Conclusions and Recommendations 157-171 Annexes I. Correspondence with the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic II. Map of the Syrian Arab Republic

I. Introduction1. As the violence escalates in the Syrian Arab Republic, the harrowing accounts of victims continue to sear themselves on the conscience of the international community. It is urgent to de-escalate the conflict and curtail the flow of weapons to allow diplomacy to end the violence.

2. In the present report, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry for the Syrian Arab Republic |a| sets out its findings based on investigations of incidents occurring between 15 January and 15 May 2013.

3. This report should be read in conjunction with previous reports of the commission (S-17/2/Add.1, A/HRC/19/69, A/HRC/21/50, A/HRC/22/59) regarding the interpretation of its mandate and working methods, as well as its factual and legal findings concerning events between March 2011 and 15 January 2013 |b|.

4. Lack of access to the country continues to hamper the commission's ability to fulfil its mandate.

5. On 28 March, the commission addressed the Permanent Mission of the Syrian Arab Republic reiterating its request to access the country and seeking information with regard to five specific incidents (see Annex I). No response was received. Since October 2012, repeated requests for meetings with the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic in Geneva have been unsuccessful.

6. The methodology employed was based on standard practices of commissions of inquiry and human rights investigations, as noted in previous reports.

7. The commission relied primarily on first-hand accounts to corroborate incidents. This report is based on 430 interviews conducted in the region and from Geneva, including via Skype and telephone with victims and witnesses inside the country. The number of interviews conducted since the mandate began in September 2011 stands at 1,630.

8. Photographs, video recordings, satellite imagery and medical records were collected. Reports from Governments and non-Government sources, academic analyses, and United Nations reports, including from human rights bodies and mechanisms and humanitarian organizations, also formed part of the investigation.

9. The standard of proof is as used in previous reports. Such standard is met when reasonable grounds exist to believe that incidents occurred as described.

The Syrian Government and the Syrian opposition

10. Syria remains engulfed in an escalating civil war. The Syrian National Dialogue Forum, launched 24 March by the Government and the domestically-based opposition to promote national reconciliation, has not shifted the momentum toward a political solution. Similarly, Presidential Decree 23 of 16 April 2013, hailed as the most comprehensive amnesty to date, has fallen short of achieving demobilisation of the Government's opponents.

11. The 21 April confirmation of Syrian National Coalition President Moaz al-Khatib's resignation, like the 13 May announcement of the creation of a new opposition group, the Union of Syrian Democrats, demonstrate deep divisions besetting the Syrian opposition abroad. Such divisions stem partly from the opposition's reliance on patrons with often-conflicting agendas.

12. The erosion of political authority and the rule of law in the country continue apace. The Government has not fulfilled its governance duties as it cannot ensure security for its citizens in areas under its rule, and it struggles to provide basic services. At the same time, a dangerous stage of fragmentation and disintegration of authority prevails in areas under anti-Government armed groups' control, despite attempts to fill the vacuum left by the withdrawal of the state through creating local councils.

13. One exception is the northeast of the country, where Syrian Kurds have unified under the Kurdish Supreme Council. Syrian Kurds are increasingly running their own affairs, whilst avoiding - whenever possible - being dragged into the fray.

Regional dimension

14. Military encroachments on sovereignty have opened the possibility of violence consuming the region. The Secretary-General of Lebanese Hezbollah has publicly asserted his group's intervention in the conflict on the side of the Syrian Government, while some Lebanese Sunni clerics have called for, and recruited, volunteers to fight in Syria. Jabhat Al-Nusra's proclamation of allegiance to Al-Qaeda, and the group's public admission of association with Al-Qaeda in Iraq, raise concerns about Syria's becoming embroiled in the global jihadist cause. The Syrian war affects the domestic political dynamics of neighbouring states and strains the relationship among their diverse communities, threatening their fragile internal stability.

15. The 11 May explosion of two car bombs in Reyhanli, in Turkey's Hatay province, close to the Syrian border, provoked an intense public debate concerning Government policy on Syria. There are fears that violence will spread increasingly to one of Turkey's most culturally and religiously mixed areas. At the 30 April Security Council meeting, Jordan's Permanent Representative stated that, at the current pace, the exodus of Syrian refugees could soon represent "a threat to our future stability." Israel has increased its involvement in the Syrian crisis by targeting what it alleges are weapons shipments bound for Hezbollah and other sites inside Syria. Exchanges of fire also occurred in the Golan Heights.

International dimension

16. The current political impasse and military escalation are the by-product of the regional and international standoff between the Government's backers and its opponents, translating into arms consignments and political backing to both sides by their respective allies. The European Union's decision to allow a ban on weapons deliveries to the Syrian opposition to lapse on 1 June, and Russia's announced shipment of S-300 missile batteries to the Government, pertains. Other international initiatives include the pro-opposition Friends of Syria meetings, and the 29 May international conference in Tehran.

17. On 7 May, Russia's Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov and US Secretary of State, John Kerry, launched a joint political initiative aimed at convening an international conference to follow-up the Geneva meeting of 30 June 2012, where a joint communique was issued. Although a date has yet to be set, an inclusive conference could break the diplomatic stalemate if it delivers a comprehensive political process to end the violence.

18. Hostilities in Syria have steadily expanded in recent months to new regions, increasingly along a sectarian divide. Brutal tactics adopted during military operations, particularly by Government forces, led to frequent massacres and destruction on an unprecedented scale. The conflict became even more complex as violence spilled over into neighbouring countries, threatening regional peace and stability.

Government forces and affiliated militia

19. Government forces continued to prioritise the control of major urban centres and main lines of communication connecting strategic regions. Excepting Al-Raqqah, the Government has held all major cities despite facing serious challenges in Aleppo, Dara'a and Dayr Al-Zawr. Recently, it launched ground operations in the Damascus countryside, Dara'a and Homs governorates to expel armed groups from strategic positions and maintain the country's main supply routes. In other operations, Government forces sought to cut supply lines connecting armed groups with their support networks in neighbouring countries.

20. Meanwhile, the army - supported by the Popular Committees - has increasingly relied upon its long-standing strategy of denying food and medical supplies to restive localities as a tactic to prevent the armed groups' expansion and to force displacement of the population.

21. In regions held by armed groups in northern and eastern governorates, Government forces resumed their brutal and often indiscriminate campaign of shelling, using a wide variety of weaponry. Besides the continuous use of aerial bombardments, they have fired strategic missiles, cluster and thermobaric bombs. This appears to be part of a broader strategy aimed at eroding civilian support for anti-Government armed groups and at damaging infrastructure. The majority of these attacks targeted towns and neighbourhoods controlled or infiltrated by armed groups, rather than targeting those groups' military bases.

22. Defections and casualties affected Government forces' strength and cohesion. To generate combat power, the Government increasingly relied on militia recently transformed into the National Defence Army, a paramilitary force. Drawn mainly from pro-Government communities, these self-defence forces have been systematically engaged in combat operations alongside army units.

23. Recently, Hezbollah fighters are openly supporting the Syrian military during operations conducted near Al-Qusayr along the Lebanese border while members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - General Command have done the same around Yarmouk camp in Damascus.

Anti-Government armed groups

24. Anti-Government armed groups have reinforced their control over regions seized in northern and eastern governorates, but failed to push further into the key areas of Damascus, Aleppo and Homs. Lacking the unity of command, operational discipline and logistical support, they have struggled in facing Government strongholds where fighting has largely stalemated.

25. The Supreme Joint Military Command Council (SJMCC), created to ensure unity of command at the national level, has failed to centralise different sources of logistical support, integrate command networks and alleviate the influence of radical groups. The inability to support its units logistically has undermined the Council's attempts to unite the armed groups under its authority.

26. Anti-Government armed groups have also conducted sporadic shelling of pro-Government areas such as Fou'a, Idlib, and imposed a tight siege on pro-Government villages in northern governorates, such as the Shi'a localities of Nubul and Zahra in Aleppo.

27. The rise in Government-supported minority militia and the positioning by both sides of bases within their respective supportive communities has fostered hostilities along sectarian lines. Provocative rhetoric, such as recent statements by the spokesperson of the Free Syrian Army, risks inciting mass, indiscriminate violence against minority communities.

28. Armed groups are still equipped mainly with small arms and light weapons, but with an increase in anti-tank and anti-aircraft systems, as well as indirect fire assets, provided predominantly by supporting countries and armed groups in the region. They used mortars and artillery guns to target army positions, but also pro-Government localities, usually those hosting army positions.

29. The on-going violence has accelerated radicalisation among anti-Government fighters, allowing radical groups, in particular Jabhat Al-Nusra, to become more influential. This group has been part of, and occasionally co-leading, most of the major operations conducted by other anti-Government armed groups given its better organisation and discipline, greater operational efficiency and access to external support. Since the announcement of ties with the Iraqi wing of Al-Qaeda, (the Islamic State of Iraq, ISI) there appears to be growing support for this group from regional extremist groups in terms of recruits and equipment. Foreign fighters with jihadist inclinations, often arriving from neighbouring countries, continued to reinforce its ranks. Tensions and clashes emerged over governance and authority matters between Jabhat Al-Nusra and local groups.

30. Other radical groups consolidated alliances that engage in significant combat operations in the north and around Damascus. With no permanent affiliation to the SJMCC, alliances such as the Syrian Islamic Front (SIF) and the Syrian Islamic Liberation Front (SILF) have developed their own governance structures, including security, political and judicial mechanisms.

Other forces

31. The People's Protection Committees (YPG) of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), officially affiliated to the Kurdish Supreme Council, has reinforced its authority over several Kurdish towns. Trying to avoid the fighting, it has sporadically clashed with both Government forces and anti-Government armed groups over control of Kurdish localities in northern and north-eastern Syria. Clashes are becoming more frequent with anti-Government armed groups despite having local military agreements and occasional coordinated joint operations, such as in Sheikh Maqsood in Aleppo.

C. Socio-economic and humanitarian context

32. According to estimates provided by United Nations humanitarian agencies, 6.8 million people, trapped in conflict-affected and opposition-held areas, and refugees in neighbouring countries are in need of urgent assistance. Half of these are children.

33. Shortages of food, medicine, fuel and electricity, especially acute in besieged cities, have gravely impacted Syrians' fundamental economic and social rights. Precarious water and sanitation conditions lead to a rising risk of summer epidemics. Destruction of hospitals in Syria's main cities severely undermined the provision of health services, particularly for individuals suffering from chronic diseases. According to UNICEF, one-fifth of the country's schools are being used for military purposes or have been converted into shelters, impacting education for hundreds of thousands of children.

34. Despite rapidly growing humanitarian needs, access to people in conflict-affected areas remains severely hindered. Humanitarian workers face bureaucratic and operational obstacles. Besides security risks, proliferation of Government and armed opposition-controlled checkpoints restricts cross-line humanitarian operations. Health care providers continue to be targeted by Government forces and members of some anti-Government armed groups.

35. The number of internally displaced Syrians is now 4.25 million. The spread of the conflict to cities once viewed as safe forced many Syrians into recurrent displacement. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) have been targeted in Homs governorate. To date, 1.6 million Syrians have become refugees. |c| Women in refugee camps face gender-based violence, including rape, forced marriages and sexual exploitation.

36. The situation of Palestinian refugees in Syria deteriorated over the past months. UNRWA estimates that 235,000 Palestine refugees are displaced. Some 53,000 and 6,000 fled to Lebanon and Jordan, respectively. Around 1,000 fled to Gaza.

37. At a conference in Kuwait on 30 January, donors pledged $1.5 billion of aid. To date, only $700 million have been secured.

III. Violations concerning the treatment of civilians and hors de combat fighters

38. Over the reporting period, 17 incidents potentially meeting the definition of massacre |d| were recorded. In the incidents discussed below, the fact of the intentional mass killing and, in some cases, the identity of the perpetrator were confirmed. Other cases remain under investigation.

Government forces and affiliated militia

Sanamayn

39. Government forces attacked Sanamayn city, Dara'a, on 10 April. Approximately 300 fighters from the opposition Martyrs of Al-Sanamayn Brigade were inside the city. As per observed patterns, the attack began with shelling followed by a ground invasion. Suffering from a lack of weapons and ammunition, the armed group withdrew from the city after heavy losses.

40. Civilians fleeing the attack appear to have been targeted and killed. Eleven members of the Al-Itmah family and seven members of the Al-Nassar family were killed when their cars were hit by shells. Multiple allegations of the use of human shields were received, but could not be corroborated. Multiple, second-hand accounts asserted that Government forces were assisted by Hezbollah fighters amid allegations of atrocities against women and children. Such information was not corroborated.

Baniyas

41. Government forces and affiliated militia attacked the village of Al-Bayda on 2 May and a neighbourhood in Baniyas, Tartous, on 3 May. Video materials show dozens of bodies of women and children apparently killed at close quarters. Evidence gathered indicates the perpetrators are Government-affiliated militia. The investigation continues.

Anti-Government armed groups

Dayr Al-Zawr

42. Eleven men appear to have executed by gunshot to the back of the head on an unknown date. A known Jabhat Al-Nusra leader from Saudi Arabia, Qassoura Al-Jazrawi, reportedly shot the men who were kneeling in front of him, hands tied and blindfolded. Al-Jazrawi claimed to be carrying out a sentence from the "Sharia Court for the Eastern Region in Dayr Al-Zawr."

Incidents remaining under investigation

Abel village

43. The village of Abel, in rural Homs, was allegedly the site of a battle between FSA and Government forces in late March. Thirteen people were killed, including five women and four children. The bodies were apparently burned.

Al-Burj

44. On 30 March, in Al-Burj, Homs, 11 people, of whom eight were women, were killed in circumstances that could amount to summary execution. Government and armed groups traded accusations.

Tartous, Homs highway

45. On 10 April, a Bedouin family staying on a roadside near an Alawite village was attacked and killed. The mother, father and seven children, all under 18, and the grandmother were murdered in their tents. Locals who filmed the scene blamed Government-affiliated militia, while distant family members appeared on television blaming "terrorist gangs."

Jdeidat Al-Fadel

46. Multiple accounts concerned incidents in Jdeidat Al-Fadel, south-western Damascus, between 15 and 24 April. Anti-Government armed groups were present in the town, which was home to thousands of IDPs. The FSA purportedly overtook a checkpoint outside nearby Jdeidat Artouz, prompting a 15 April Government military operation by the 100th Regiment and 4th Division. Access to the area was blocked by Government snipers. As fighting intensified, the civilian population and hundreds of opposition fighters were trapped inside. Individuals fleeing were killed, though it could not be confirmed whether they were fighters or civilians. Multiple allegations of extrajudicial executions of anti-Government fighters were recorded.

Nubul

47. Nubul, a Shi'a village in Aleppo, has been under siege by anti-Government armed groups since July 2012. In an effort to bring food and medicine to the village, and acting on information that passage would be allowed, 30 to 40 men from Nubul left for Afrin in mid-April. Near Al-Ziyara village the convoy was ambushed and 15 to 20 men were killed and the rest detained. Evidence indicates that some of the men in the convoy may have been lightly armed as protection against attack. The commission could not confirm the circumstances, and therefore the legality, of their deaths. Allegations that the bodies were mutilated were uncorroborated.

Khirbat Al-Souda

48. Government forces entered Khirbat Al-Souda, western Homs, on 15 May in an apparent effort to attack opposition forces there. Allegations of summary execution arose afterwards based in part on video evidence.

Execution of prisoners in three governorates

49. Investigations are on-going as to whether, in response to an attack by anti-Government armed groups, security officials in Gherz central prison in March, Sednaya prison in April and Aleppo prison in May, executed inmates in an attempt to stave off attack.

50. Reasonable grounds exist to believe that the war crime of murder has been committed in two massacres perpetrated by Government forces and affiliated militia and one perpetrated by anti-Government armed groups. The killing in Baniyas and Sanamayn fit the pattern of widespread attacks on a civilian population by the Government and may therefore amount to murder as a crime against humanity. In incidents that remain under investigation, the fact of the killing was confirmed. However, neither the perpetrator nor the circumstances could be determined.

Summary execution and the war crime of murder

51. Patterns of summary execution and murder have emerged. Detained persons believed to be opposition sympathizers are the most frequent victims of such crimes. Revenge killings have become increasingly common and are a direct violation of the prohibition on reprisals. Killing civilians by sniper fire and killing of hostages and detainees when a detention centre comes under attack are noted patterns of violations by both pro and anti-Government groups.

Government forces and affiliated militia

52. Over 200 bodies have been recovered from Aleppo's Queiq waterway since 81 bodies were first discovered there on 29 January. One doctor described personally seeing 140 bodies. Many victims had gone missing in Government-controlled areas of the city. Some of those recovered had been in either Air Force Intelligence or Military Intelligence detention. Family members discovered this by paying bribes to the intelligence agencies for unofficial information or because other detainees released from these facilities confirmed their presence.

53. In Dara'a, two men were detained in a house occupied by Military Security in Al-Shajarah in January. Military Security withdrew on 16 March. The following day, relatives found the men in the house, shot dead and bearing clear signs of torture. In January, two men were shot dead at a checkpoint near Kherbet Ghazalah bridge and a third was heavily injured. The injured man was then killed by soldiers.

54. Field executions continued to be reported during large-scale military operations. One interviewee, whose regiment conducted operations in Al-Waar and Bab Amr in Homs, described executing civilians, including two young children, in their homes so that they would not give away the soldiers' locations to nearby FSA fighters.

Anti-Government armed groups

55. Video footage emerged showing a child participating in the beheading of two kidnapped men. Following investigation, it is believed that the video is authentic and the men were soldiers, killed as depicted. It was not possible to identify the perpetrators. Evidence indicates the Usud Al-Tawhid Brigade committed the initial kidnapping.

56. Three separate incidents of killing by sniper fire attributed to anti-Government armed groups were recorded in Damascus. In February, and on 7 and 20 April, three youth, including one toddler, were killed in Sayda Zaynab. On 19 April, another youth was killed in Al-Bahdaliya.

57. Government forces and affiliated militia as well as anti-Government armed groups have perpetrated the war crime of murder and the human rights violation of summary execution. Murders by Government forces formed part of a widespread attack against a civilian population amounting to a crime against humanity. Despoiling bodies of the deceased, including through burning and mutilation, is a war crime perpetrated by individuals on both sides.

The war crime of sentencing or execution without due process

Anti-Government armed groups

58. Over the past six months, armed groups have established judicial and administrative mechanisms across Aleppo, Dara'a, northern Idlib, Al-Raqqah, Al-Hasakah, Dayr Al-Zawr and parts of eastern Damascus governorate, attempting to fill the vacuum created by the absence of Government institutions.

59. In Aleppo, Damascus, Dara'a, Idlib, Dayr Al-Zawr and Al-Raqqah governorates, persons - civilians and hors de combat Government soldiers - were sentenced and executed without due process. Armed groups apply the loose standard of "having blood on one's hands" to denote responsibility for criminal conduct deserving the death penalty.

60. In Dara'a and Al-Raqqah, armed groups used public show trials and executions of detainees affiliated with the Government to assert their authority and instil fear among civilians. In Yarmouk camp, Damascus, two persons accused of being Government collaborators were hanged in a public square on 3 March without recourse to a regularly constituted court. On 14 May, fighters claiming to be from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant executed three Alawite men in a public square in Al-Raqqah city. The judgment stated that the execution was a reprisal for the massacre in Baniyas and Homs on 2 and 3 May. A series of trials in Al-Raqqah city and in Al-Shajarah, Dara'a, in April had sectarian dimensions. Witnesses stated that captured Alawite soldiers were consistently found guilty and executed, while non-Alawites were imprisoned or released.

61. In Aleppo, divisions among armed groups compromised efforts to establish a cohesive justice system. Attempts to establish independent civilian law enforcement structures were obstructed by armed group commanders wary of interference in their interests. Failure to agree on an applicable body of law means order is enforced arbitrarily, and courts are not regularly constituted.

62. Two competing bodies administer justice in Aleppo. The Judicial Council applies legal doctrine derived from regional sources of law, while the Shari'a Board applies interpretations of Islamic law. Both have close functional links to the FSA, compromising their impartiality and independence, while the provision of basic guarantees essential to fair trial varies widely. According to one interviewee, the Shari'a Board in Aleppo does not permit defence lawyers to participate in the proceedings.

63. The war crime of sentencing and execution without due process was committed by armed groups in Aleppo, Damascus, Dara'a, Idlib, Dayr Al-Zawr and Al-Raqqah. In the cases described, sentences were passed and persons - who were either hors de combat or civilians - were executed with no previous judgment pronounced by a court providing the judicial guarantees generally recognised as indispensable under international law.

C. Arbitrary arrest and detention

Government forces and affiliated militia

64. Government forces continue to use deprivation of liberty as a weapon of war, and to collectively punish localities perceived to be supporting the armed opposition.

65. Family members of alleged armed group members are arrested and detained. In one documented incident on 10 April, a man whose brother was wanted for arrest was detained by the 1st Division at a checkpoint at the entrance to Kesweh, Damascus, to coerce him into providing information about his brother.

66. Government forces routinely arrest and detain persons as punishment for exercising their basic rights. In mid-January, following a peaceful demonstration in Al-Suwayda, security forces conducted mass arrests. Some of those arrested were children as young as 12.

67. In Um Walad, Dara'a, Government military and security forces arrested men at checkpoints on the sole criteria of being of military age. Since January, while raiding predominantly Sunni neighbourhoods in Latakia city, Government forces detained men, women and children. After holding them for a prolonged period, they were released without charge and without being informed of the reason for their detention.

68. Government forces conducted widespread arbitrary arrests of persons, in areas where they have re-asserted control. In mid-January, Government forces arrested students, including children, due to their perceived loyalty to the armed opposition following a ground assault on Egeirbat, eastern Hama. Government forces carried out a similar wave of arrests in Nawa, Dara'a in mid-March. In April, during a ground assault on Sunni villages around Al-Qusayr, Homs, Hezbollah fighters arrested more than 50 civilians during house searches.

69. Syria's armed forces have broad, unchecked powers to detain civilians they suspect of harbouring opposition loyalties. The arrest or detention of persons as punishment for exercising fundamental human rights is per se arbitrary. Arrests conducted on discriminatory grounds, such as the religious or geographic origin of persons, also violate international human rights law. The arrest and detention of all men of fighting age is an indication of arbitrariness, and the mass arrest of civilians, including women, children and the elderly, in areas perceived as supporting the opposition, amounts to collective punishment and is illegal under international humanitarian law.

70. There has been a dramatic rise in hostage-taking. Often sectarian in nature, it sparks reprisals and fuels inter-communal tensions. Foreigners, including journalists, businessmen and peacekeepers, have also been seized. Families can ill-afford the ransom, and the consequences of non-payment have been lethal.

Government forces and affiliated militia

71. The Commission investigated but did not confirm allegations that the army and Popular Committees took hostages in Kesweh, Damascus, and Muzayrib, Dara'a, in April. In Muzayrib, in April, civilians held by the army on a bus were threatened with death unless the FSA ceased attacks.

Anti-Government armed groups

72. UN Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) and UN Truce Supervision Organisation (UNTSO) members were seized on 6 March by the Al-Yarmouk Martyrs Battalion near the Golan Heights. The same group seized four UNDOF peacekeepers on 7 May. A third incident occurred days later when 18 anti-Government fighters held three UNTSO peacekeepers in the Area of Separation between Israel and Syria. In all three cases the kidnappers were seeking to leverage the hostages to halt a Government attack. All were released unharmed.

73. In February, anti-Government armed group members abducted a Sunni male in Damascus, mistaking him for an Alawite officer. He was tortured and suffered sectarian epithets and other derogatory language before eventually persuading his captors that he was the wrong man. Nevertheless, his family was forced to pay a ransom.

74. Kidnappings have markedly increased in Aleppo and northern Syria in areas beyond Government control. Two lawyers from the besieged town of Nubul were kidnapped in February while returning from Afrin with a delivery of flour. They are still being held by members of Ahrar Al-Sham. A detention facility run by Al-Badr Martyrs Brigades in Hayan contains dozens of people being held for ransom.

75. On 9 February, two Aleppo priests, one Greek Orthodox and one Armenian Catholic, were abducted at an anti-Government checkpoint. On 22 April two Aleppo bishops, one Greek Orthodox and one Assyrian Orthodox, were abducted by unidentified gunmen. The bishops' driver was shot and killed. The gunmen have not been identified. Other anti-Government armed groups have attempted to find the priests, who remain missing.

76. In Dara'a in mid-May, anti-Government armed groups reportedly abducted the Syrian Deputy Foreign Minister's 84-year-old father. No group has claimed responsibility.

77. Anti-Government armed groups have kidnapped individuals and held them hostage in violation of Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, amounting to a war crime.

Government forces and affiliated militia

78. Enforced disappearances were carried out by Government officials, including Military Intelligence, and by affiliated militia acting on behalf of or with the support of the Government.

79. Large numbers of individuals, mainly young men, were arrested at Government and affiliated militia-controlled checkpoints throughout the country including in Shin, Homs; in Nawa, Dara'a; and in Qatana, Damascus, and held for prolonged periods. Some were taken to unknown locations and have not been heard from since. In other cases, arrests were followed by a refusal by Government officials to disclose the whereabouts of the persons concerned. In most cases relatives did not try to ascertain the fate of those arrested due to well-founded fears of reprisals.

80. Such acts place the persons concerned outside the protection of the law in violation of their fundamental rights to liberty and security, and constitute a threat to their right to life. Such victims face torture and ill-treatment. Depriving detainees of contact with the outside world causes continuing anguish to their families.

81. Government forces and affiliated militia perpetrated enforced disappearance. Where part of a widespread or systematic attack on a civilian population, these enforced disappearances constitute a crime against humanity.

F. Torture and other forms of ill-treatment

Government forces and affiliated militia

82. Torture is endemic across detention centres and prisons. At the Military Police headquarters in Latakia, Government security officers beat, slapped repeatedly and kicked an opposition activist. She was humiliated and verbally abused. Other detainees in the same facility were tortured regularly and held in cramped cells containing vermin and insects. Detainees were stripped naked, subjected to electrical shocks and suspended for prolonged periods from the ceiling by the arms with their toes barely touching the ground ('Shabh'). One survivor stated, "death is better."

83. Detainees held at Latakia's Military Security Branch are systematically tortured, beaten with batons and cables, punched, kicked and subjected to 'dulab', in which persons are forced into a tyre and beaten.

84. Persons detained at the Military Security branch in Dara'a were consistently subjected to electric shocks, beatings and stretching of limbs with the Busat Al Rih method. Hundreds of detainees were held in dangerously over-crowded conditions, forcing them to sleep standing up. In a facility operated by the 38th Regiment in Bosra, Dara'a, detainees were subjected to Shabh, had boiling water poured on them and electric shocks administered.

85. In an underground facility in Branch 285, the General Intelligence Directorate in Damascus, hundreds of detainees are held in deplorable conditions in cramped cells. Detainees are denied medical care and the health and hygiene needs of female detainees are ignored. Victims described how guards routinely beat detainees at 7pm each day and used the Shabh, Dulab, Busat Al Rih and Falaqa torture methods.

86. Detainees held in Adra Prison, northeastern Damascus, and in Homs Central Prison, suffered from inadequate food, water, insufficient sanitary installations and a total absence of medical care. In Adra Prison, detainees were held in inhumane and degrading conditions in cramped cells. Detainees released from the Military Security and Air Force Intelligence prisons in Al-Raqqah city and the Military Security Branch detention centre in Al-Tabqah, Al-Raqqah, bear extensive signs of torture.

87. The ill-treatment described by victims detained in Government prisons and facilities amounts to cruel treatment and torture. Government officials wilfully cause great suffering and serious injury to body and health, using torture to instil fear, extract confessions and punish. Such conduct amounts to a violation of Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions and is a war crime. The systemic ill-treatment and torture documented in detention centres across Syria evidence a state policy of torture, constituting a crime against humanity.

Anti-Government armed groups

88. Torture has been documented in detention facilities run by the Judicial Council and the Shari'a Board in Aleppo. Detainees suspected of being Shabbiha were subjected to severe physical or mental pain and suffering to obtain information or confessions, or as punishment or coercion.

89. In contested areas, persons have been beaten at checkpoints controlled by anti-Government armed groups. In January, Jabhat Al-Nusra fighters arrested a man on the road from Saraqib, Idlib to Aleppo, on the suspicion that he was Shi'a. He was detained for three days. When released, he bore extensive bruises and other signs of torture. At an FSA checkpoint in Aleppo city, persons perceived to be supportive of the Government were harassed and subjected to beatings and other ill-treatment.

90. Severe ill-treatment for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, amounts to torture and is a violation of international humanitarian law. The war crime of torture and cruel treatment has been perpetrated by Jabhat Al-Nusra fighters and other anti-Government armed groups.

91. Sexual violence has been a persistent feature of the conflict. Chronic under-reporting has made judging the magnitude of this violation difficult. Fear of rape is a driving motivation for families fleeing the violence.

Government forces and affiliated militia

92. When committed by pro-Government forces, sexual violence occurred during house searches, at checkpoints and in detention centres, often as part of interrogations by intelligence services. One woman detained in Latakia, described how she was threatened with gang rape during her interrogation. She also described other detainees being stripped naked while subjected to electric shocks. In Branch 285, the rape and sexual abuse of male detainees by their interrogators was reported. There were no indications of action taken by senior commanders to investigate, prevent or punish acts of sexual violence.

93. Rape and other inhumane acts, as crimes against humanity, have been committed by Government forces and affiliated militia. Rape, torture and inhumane treatment are prosecutable as war crimes.

Anti-Government armed groups

94. A limited number of interviews describe women being segregated during house searches in Aleppo city, in joint operations by armed groups, with an implication of possible sexual violence. One interviewee stated she had been the victim of a sexual assault in Yarmouk, Damascus, in April.

95. During the assault in Yarmouk, the war crime of sexual violence was committed. Based on limited information, it was not possible to reach a finding in relation to the other accounts.

H. Violations of children's rights

Unlawful killings and injuries

Government forces and affiliated militia

96. Children continue to be the victims of shelling and aerial bombardments by Government forces. Examples include attacks on Kaljabrin, Aleppo on 23 January; Al Huwash, Hama on 7 February; Saa'sae, Damascus on 28 and 29 March; Al Houlah, Homs on 29 March; and Sanamayn, Dara'a on 10 April. In late February, a 14-year-old child was shot by a sniper positioned in the Ba'ath party offices in Dara'a Al-Balad.

97. Government sieges have led to health and nutrition crises that disproportionately affect children under five and nursing mothers. A clinician in Al-Houlah said that thirteen children died between August 2012 and April 2013 from malnutrition and lack of medication.

Anti-Government armed groups

98. Children were killed in attacks by armed groups. In April, a two-year-old boy died after being shot by a sniper firing from an opposition neighbourhood while on a street in Sayda Zaynab, Damascus. A 12-year-old boy in Nubul, Aleppo, was killed during rocket attacks in April by armed groups besieging the town. Child malnutrition increased in Nubul.

Abductions, arbitrary arrests, detention and torture

Government forces and affiliated militia

99. Government forces and militia detained children at checkpoints and during house raids. Several arrests in Dara'a appeared to target children of suspected FSA members. Others held children as hostage in exchange for detainees held by the FSA. During the 10 April attack on Sanamayn, children were forced to watch the torture or killing of parents. In April, checkpoint personnel in Rastan, Homs, threatened to shoot two girls aged nine and seven who started crying during their father's interrogation.

Anti-Government armed groups

100. In December 2012, a woman and her six-year-old daughter were kidnapped from Al-Fou'a, Idlib and held in an underground detention facility in Saraqib. They were released in January on payment of ransom to Jabhat Al-Nusra.

Recruitment and use of children

Anti-Government armed groups

101. Some armed groups recruit and use children for active participation in hostilities. A 14-year-old boy from Homs underwent training in use of weapons with the Abu Yusef Battalion, which then used him to keep track of soldiers' movements in Al-Waar. Other groups reject underage volunteers. Commanders in Dayr Al-Zawr refused to accept a 15-year-old boy, calling his parents to collect him.

102. Casualty statistics indicate 86 children were killed in hostilities as combatants. Of those, nearly half died in 2013. These figures suggest the use of children in combat is increasing.

IV. Violations concerning the conduct of hostilities

103. Civilians bear the brunt of violent and often indiscriminate attacks. Government forces continued their campaign of shelling and aerial bombardment. Instances of armed groups shelling Shi'a enclaves in Aleppo, Idlib and Damascus governorates were recorded. There were multiple bombings, mainly in Damascus, for which no party claimed responsibility.

Government forces and affiliated militia

104. Government forces conduct their military operations in flagrant disregard of the distinction between civilians and persons directly participating in hostilities. Extensive aerial and artillery capabilities continue to be deployed. Increasingly even less precise weaponry such as surface-to-surface missiles, thermobaric bombs and cluster munitions are being used. There is a strong element of retribution in the Government's approach, with civilians paying a price for "allowing" armed groups to operate within their towns.

105. Attacks by artillery shelling, barrel bombs and aerial bombardment were particularly fierce in heavily contested areas of strategic importance, such as Aleppo and Homs cities. Yarmouk, Damascus has been heavily shelled, leading to the exodus of Palestinian refugees into Lebanon. Such attacks did not discriminate between military targets and civilian objects, and occurred across the country in numerous locations. Areas more firmly under anti-Government armed group control, such as Al-Raqqah city and Dayr Al-Zawr villages, continue to suffer shelling and bombardment. There were multiple accounts of surface-to-surface missiles causing massive destruction in northern Syria, as occurred in Ard Al-Hamra neighbourhood on 23 February and Hreitan, Aleppo on 29 March. Thermobaric bombs were used in Al-Qusayr on 20 March. Cluster munitions were used in numerous locations, including Qarah, rural Damascus, between 3 and 6 April.

106. Towns in northern Aleppo and Idlib governorates have been largely emptied of civilians, turning them into de facto military zones. It is clear that the Government could take greater precautions to protect civilians that remain. In May, shortly before the attack on Al-Qusayr, Government forces dropped leaflets advising civilians to leave the area. In the context of Government attacks, such precautions remain an anomaly.

107. Multiple accounts were received - from former residents of towns across Dara'a, Sha'ar and Ashrafiyah neighbourhoods, Aleppo, and Yarmouk, Damascus - of snipers targeting persons, without distinction. Casualties include women and children.

108. Government forces consistently transgressed the fundamental principle of the laws of war that they must at all times distinguish between civilian and military objectives.

Anti-Government armed groups

109. Armed groups continue to operate within civilian areas. This endangers the civilian population and violates international legal obligations to avoid positioning military objectives within or near densely populated areas. Some armed groups take precautions to safeguard the civilian population. On 6 February, in Al-Tabqah, Al-Raqqah, fighters warned residents to evacuate the area in advance of an attack. Prior to the May attacks on Al-Qusayr, armed groups assisted in the evacuation of civilians.

110. There are isolated instances of armed groups' shelling towns and villages, usually under the pretext that the attacks are directed against Government forces. On 24 April and on 4 and 6 May, Liwa Al-Tawhid, Ghuraba Al-Sham and Jabhat Al-Nusra fired scores of mortars and homemade rockets into Nubul and Zahra, Aleppo. There were multiple civilian casualties, including a 12-year-old boy. In February, armed groups in Aleppo city fired mortars into Government-controlled areas. In March, groups fired mortars into Sayda Zaynab and surrounding neighbourhoods of Damascus. They shelled Fou'a, Idlib throughout 2013. All areas attacked had a majority Shi'a population. There are reports of snipers from armed groups firing into Nubul and Sayda Zaynab throughout early 2013, causing civilian casualties.

111. Anti-Government armed groups used mortars, rockets and snipers in a manner that failed to distinguish civilian and military objectives, committing unlawful attacks.

Undetermined perpetrators

112. The use of improvised explosive devices - usually car bombs - continued. All but one attack took place in Damascus. The first attack, on 15 January, was the bombing of Aleppo University, which killed over 80 people. Bombs exploded in Damascus on 21 February near the Ba'ath party headquarters and in the Barzeh neighbourhood; on 21 March at the Al-Iman mosque; on 8 April near the Central Bank; on 29 April near the former Interior Ministry and 30 April in central Damascus. No party claimed responsibility.

113. With the exception of the bombing in Barzeh neighbourhood - where the majority of casualties were soldiers - the bombings demonstrated no clear military objective. The attacks spread terror among the civilian population. The high number of civilian deaths and injuries evidenced a disregard for human life.

114. As armed factions in Syria proliferated, it is increasingly difficult to determine the perpetrators of such attacks. While these acts constitute crimes under domestic law, they may also amount to war crimes, if it is determined that the perpetrators are parties to the conflict.

B. Specifically protected persons and objects

Historic objects

115. On 13 April, the 7th century minaret of the Al-Omari mosque in Dara'a came tumbling down. On 24 April, the 12th century minaret at Aleppo's Umayyad mosque collapsed, after being shelled. Government forces and anti-Government armed groups have traded blame.

116. Across Syria, historic monuments are being damaged and destroyed. No party to the conflict is abiding by its obligation to respect cultural property and to avoid damage to this property in the context of military operations. Both Government forces and anti-Government armed groups have rendered sites open to attack by placing military objectives in them.

117. The army has established bases in the ancient citadels of Aleppo, Homs and Hama. Anti-Government armed groups are based near the edges of Aleppo's citadel, placing it at risk of further damage. In Maaret Al-Numan, in north-western Idlib, an armed group based itself in a 17th century caravan trading post, which had been a museum. Nearby artefacts were destroyed by shelling.

118. The Roman ruins of Bosra, Dara'a, have been damaged, as have ruins in the ancient desert city of Palmyra. The outer walls of the Krak des Chevaliers, a Crusader fortress in Homs, were marred by rocket fire. According to UNESCO, five of Syria's six World Heritage sites have been damaged.

119. Looting, sometimes committed by parties to the conflict, has ravaged historic sites. Byzantine mosaics in the "dead cities" of northern Syria and the Roman city of Apamea were removed. Interpol lists an 8th century B.C. Aramaic bronze statue, stolen from the Hama museum.

Religious objects

120. On 17 January, the Kafr Nabudah mosque, Hama, was shelled. The shelling of the Bilal mosque in Al-Habit, Idlib, on 27 January and 7 February followed. In the 21 April attack on Jdeidat Al-Fadel, Damascus, Government forces burnt the mosque. Where attacks on the mosques had no military objective, the war crime of attacking protected objects was committed.

121. In early January, fighters from an anti-Government armed group looted and destroyed Al-Husseiniya, a Shi'a religious centre in Al-Tabqah, Al-Raqqah. On 11 February, a nearby Orthodox church was looted and destroyed. Armed groups in Al-Tabqah committed the war crime of attacking protected objects.

Hospitals and medical personnel

122. The deliberate targeting of medical personnel and hospitals, and denial of medical access, continue to be a disturbing feature of the conflict.

123. State and field hospitals in Jasem and Tafas, Dara'a; Adra, Damascus countryside; Hajar Al-Aswad and Yarmouk, Damascus; Sha'ar and Ansari neighbourhoods, Aleppo have been the subject of shelling and aerial bombardment by Government forces. Some, such as Zarzor hospital in Ansari, have been hit repeatedly. Some State hospitals have been used as military bases by Government forces. Snipers are positioned at Al-Houlah's hospital, with tanks and artillery at its entrance.

124. Medical personnel have come under attack. Zarzor hospital staff went missing and are reportedly being held by Air Force Intelligence in Aleppo. A nurse in a field clinic in Homs was wanted for arrest because he provided medical assistance to armed groups.

125. In Aleppo and Homs, accounts were received of wounded and sick being refused medical treatment on political and sectarian grounds. Civilians avoided seeking treatment in Government-administered hospitals due to a well-founded fear of arrest. One doctor in an Aleppo hospital described arrests of injured young men by security forces.

126. Government forces committed the war crime of attacking protected objects and the war crime of attacking objects or persons using the distinctive emblems of the Geneva Conventions.

C. Pillaging and destruction of property

127. Justifying their actions either as "spoils of war" or as retribution for supporting the opposing side, parties to the conflict burn, loot and pillage homes and businesses. The ever-increasing refugee and IDP populations leave behind belongings, which are then appropriated by soldiers and armed groups.

128. Fleeing families attempting to take their possessions with them frequently have them stolen at checkpoints or by thieves taking advantage of the lawlessness. While vast amounts of property have been destroyed as a result of shelling, a violation is recorded when reasonably believed to be a deliberate targeting of an opponent's property. Both pillage and deliberate property destruction are war crimes.

Government forces and affiliated militia

129. In a now familiar pattern, following shelling and ground attacks, Government forces and Shabbiha secure an area and conduct house searches. While inside homes they steal valuables, irrespective of whether the occupants are present. At checkpoints, cars and money are taken from those coming from known opposition neighbourhoods.

130. Prolonged fighting in Dara'a has displaced tens of thousands, leaving homes and businesses unguarded. Dara'a city, Sanamayn (April), Um Waleed (April), Jasem, Musayfrah, and Al-Abassiyah (all in February), have had the homes of suspected anti-Government sympathisers stripped bare. In many cases the theft is followed by burning of the homes and businesses.

131. On the outskirts of Hama in early April, an IDP returned home a month after her village was bombed and raided by Government forces. She found her house and car had been burnt, as had those of her neighbours. Items, such as televisions and furniture, had been looted.

Anti-Government armed groups

132. During the March fighting in Al-Raqqah city, the Shi'a and Alawite communities fled. Most have not returned. Their homes were confiscated by armed groups, their properties looted and the items sold off. Looting of the homes of loyalists was rampant in Al-Tabqah, when anti-Government groups, including Jabhat Al-Nusra, took over in February. The Orthodox church and its bishop's home were looted and much of the church property destroyed.

133. In Yarmouk, Damascus, armed groups have either stolen cars and trucks, or coerced residents into giving them up. In Aleppo, groups at checkpoints steal from Alawite or Shi'a civilians.

134. The "Islamist Sharia Commission" in Aleppo and Jabhat Al-Nusra in Yarmouk and in Idlib have attempted to curb such theft, arresting or expelling members of some of the groups involved.

135. Anti-Government armed groups and Government forces and affiliated militia have committed the war crimes of pillage and destruction of property.

136. As the conflict escalates, the potential for use of chemical weapons is of deepening concern. Chemical weapons include toxic chemicals, munitions, devices and related equipment as defined in the 1997 Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and Their Destruction. Also applicable is the 1925 Geneva Protocol which Syria has ratified. |e| The use of chemical weapons is prohibited in all circumstances under customary international humanitarian law and is a war crime under the Rome Statute.

137. The Government has in its possession a number of chemical weapons. The dangers extend beyond the use of the weapons by the Government itself to the control of such weapons in the event of either fractured command or of any of the affiliated forces gaining access.

138. It is possible that anti-Government armed groups may access and use chemical weapons. This includes nerve agents, though there is no compelling evidence that these groups possess such weapons or their requisite delivery systems.

139. Allegations have been received concerning the use of chemical weapons by both parties. The majority concern their use by Government forces. In four attacks - on Khan Al-Asal, Aleppo, 19 March; Uteibah, Damascus, 19 March; Sheikh Maqsood neighbourhood, Aleppo, 13 April; and Saraqib, Idlib, 29 April - there are reasonable grounds to believe that limited quantities of toxic chemicals were used. It has not been possible, on the evidence available, to determine the precise chemical agents used, their delivery systems or the perpetrator. Other incidents also remain under investigation.

140. Conclusive findings - particularly in the absence of a large-scale attack - may be reached only after testing samples taken directly from victims or the site of the alleged attack. It is, therefore, of utmost importance that the Panel of Experts, led by Professor Sellstrom and assembled under the Secretary General's Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons, is granted full access to Syria.

141. Siege warfare has entered the arsenal of the parties to the conflict. Government forces and affiliated militia have systematically employed sieges across the country, trapping civilians in their homes by controlling the supply of food, water, medicine and electricity. In some instances, anti-Government armed groups have also employed this tactic.

142. There is a clear prohibition on the use of starvation as a method of warfare under the laws of war. In the context of a siege, inhabitants must be allowed to leave and the besieging party must allow free passage of foodstuffs and other essential supplies. Parties to the conflict must allow and facilitate the unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief.

Government forces and affiliated militia

143. Government forces lay siege to areas with a heavy presence of anti-Government armed groups to contain their operational forces and compel withdrawal. The blockade of Yarmouk, Damascus, was tightened in January. Food and medicine to the remaining 10,000 residents is strictly rationed with bread limited to two bags for each family, irrespective of size. The prolonged siege of the Al-Houlah villages, Homs, has harrowing consequences on the lives of civilians trapped therein. A former resident witnessed a baby die of malnutrition and said food shortages had affected nursing mothers. The sick and wounded cannot be evacuated from Al-Houlah, while lack of medication at the field hospital has forced doctors to resort to desperate measures, including amputations.

144. Government forces also impose sieges upon towns and villages considered sympathetic to the opposition or containing anti-Government armed group fighters, as a tactic of attrition. Settlements in southern Dara'a have been subject to blockades where Government forces cut off food, electricity, fuel, water and medical supplies. Al-Shajarah town, near Dara'a, was besieged from February to April, following intensive shelling which caused many to flee. Government forces surrounded the remaining civilians, suggesting a punitive element to the deprivation of access to food and medicine. Such sieges appear calculated to render the conditions of life unbearable, forcing civilians to flee and exposing anti-Government armed group fighters as military targets.

145. Towns in strategic locations have also been tightly surrounded and sealed to create a buffer against armed opposition infiltration. In cooperation with military forces, Popular Committees have prevented food supplies from entering Nawa, Dara'a; and Kesweh and Qatana in Damascus.

146. Government forces and affiliated militia have imposed sieges and blockades on towns without complying with their obligations under international humanitarian law.

Anti-Government armed groups

147. Anti-Government armed groups have besieged Shi'a enclaves in predominantly Sunni areas, claiming they host Government military forces. Since July 2012, anti-Government armed groups in Aleppo have surrounded Nubul and Zahra, blocking food, fuel and medical supplies to 70,000 residents. As the siege tightened in recent months, the population, especially women and children, began to suffer malnutrition. The wounded and sick cannot receive medical treatment. Persons attempting to leave the villages are often kidnapped, held for ransom or killed.

148. The manner in which anti-Government armed groups have laid siege violates their obligations under international humanitarian law.

149. In Syria, hundreds of thousands of civilians are on the move, searching for ever-dwindling safe havens. Many are fleeing aerial bombardments and ground attacks by Government forces. Others - often, but not exclusively, from the Alawite, Shi'a, Druze and Christian communities - are fleeing attack by anti-Government armed groups. Within this context, specific instances of forcible displacement have been recorded.

150. In March and April, internally displaced civilians - predominantly from Homs governorate - sought refuge in Deir Atiyah, a town in northern Damascus. Between 19 and 23 April, Government forces shelled Deir Atiyah and sent a message to the town's authorities that the internally displaced were to be forced to leave the town. Failure to do this would result in the town's being attacked. In late April, the municipal office of Deir Atiyah informed the displaced that they had four days to leave before their quota of bread was withdrawn. Shortly thereafter, there was an exodus of internally displaced persons, many from Homs city and Al-Qusayr, from Deir Atiyah.

151. Indiscriminate bombardment of civilian locations constitutes an attack on a civilian population. Such attacks are widespread in Syria and undertaken by Government forces pursuant to an organizational policy. The forcible displacement of those who sought refuge in Deir Atiyah was undertaken by perpetrators with knowledge of such attacks and therefore constitutes a crime against humanity. The war crime of displacing civilians has also been committed.

152. A review of evidence collected since January has satisfied the commission that the gravity of the crimes committed by Government forces and affiliated militia and anti-Government armed groups, the prevalence of such crimes and the alarming rate at which they continue to be perpetrated lends force to the Commission's recommendation that there must be a referral to justice at the national and international levels.

153. The discussions surrounding the prospect of an international conference have been silent on the issue of accountability. While such diplomatic efforts may signify a significant step towards breaking the impasse in Syria, the imperative to stop the violence cannot obscure the reality that there can be no enduring peace without justice.

Government forces and affiliated militia

154. Over the reporting period, consistent and corroborated accounts indicated that Government forces committed gross violations of their obligations under international human rights law and Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, perpetrating war crimes and crimes against humanity. The documented violations are consistent and widespread, evidence of a concerted policy implemented by the leaders of Syria's military and Government.

155. There have been no convincing domestic efforts to investigate these crimes or to bring those responsible to justice. The international community also bears the burden of having so far failed to ensure accountability for the perpetrators.

Anti-Government armed groups

156. Evidence collected indicates that several individuals in anti-Government groups committed war crimes in violation of their obligations under Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions. The take-over of Al-Raqqah in March ushered in a period of lawlessness in the conduct of anti-Government armed groups as they turned to violence to assert their authority. The commanders of anti-Government armed groups have consistently failed to take appropriate disciplinary steps, and in most cases, were directly involved in the commission of crimes.

VI. Conclusions and Recommendations

157. There is a human cost to the political impasse that has come to characterise the response of the international community to the war in Syria. The desperation of the parties to the conflict has resulted in new levels of cruelty and brutality, bolstered by an increase in the availability of weapons. Increased arm transfers hurt the prospect of a political settlement to the conflict, fuel the multiplication of armed actors at the national and regional levels and have devastating consequences for civilians.

158. The erosion of the State and the political authority in parts of the country is compounded by the fractious nature of the various parties claiming control of the territory. Syrians are confronted with intensifying damage, displacement and despair. War rages at key flashpoints, deepening the sectarian divide and spilling over into neighbouring countries.

159. We thus reiterate the following concerns. While the nature of the conflict is constantly changing, there remains no military solution. The conflict will end only through a comprehensive, inclusive political process. The international community must prioritise a de-escalation of the war and work within the framework of the 2012 Geneva Communique.

160. All parties are obliged to respect human rights and international humanitarian law. Both they and their supporters share the responsibility to commit to a peaceful solution.

161. Accountability must be re-emphasised at all levels.

162. Humanitarian access should be sustained and enlarged, with full commitment from all parties.

163. We renew the recommendations in our earlier reports and highlight those which follow.

164. To the International Community:

a) Support the peace process based on the Geneva Communique and the work of the UN and Arab League Joint Special Representative for Syria;

b) Ensure that any peace negotiation is conducted within the framework of international law, cognizant of the urgent need for a referral to justice at the national and international levels;

c) Commit to ensuring the preservation of material evidence of violations and international crimes to protect the Syrian peoples' right to truth;

d) Counter the escalation of the conflict by restricting arms transfers, especially given the clear risk that the arms will be used to commit serious violations of international human rights or humanitarian law. States that exercise influence on the parties to the conflict must take real and tangible steps to curb the increasing influence of extremist factions;

e) Sustain and increase the funding for humanitarian agencies and operations inside the country as well as help neighbouring countries affected by the situation and secure the $1.5 billion of aid pledged at the 30 January donor conference in Kuwait.

165. To all parties:

a) Reject sectarian rhetoric as a tactic of war;

b) Commit to ensuring the preservation of material evidence of violations and international crimes to protect the Syrian peoples' right to truth;

c) Allow immediate and full humanitarian access by humanitarian organizations to all areas affected by fighting.

166. To the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic:

a) Constructively participate in the peace process guided by a commitment to human rights, democracy and a genuine desire for peace;

b) Allow the Commission, as well as the Secretary-General's Mechanism for Investigation of Alleged Use of Chemical and Biological Weapons, to enter the country and conduct investigations;

c) Respect human rights and international humanitarian law, upholding basic principles such as the need to prevent indiscriminate attacks on the population.

167. To the anti-Government armed groups:

a) Join the peace process in a constructive spirit, presenting a unified position guided by shared commitments;

b) Reject extreme elements, and compel all groups to respect human rights and international humanitarian law.

168. To the OHCHR and other UN agencies:

a) Consolidate the presence of the OHCHR in the region, in coordination with other UN agencies, in the pursuit of peace, democracy and human rights;

b) Reinforce the protection of civilians through effective, inter-agency UN presence in the country.

169. To the UN Human Rights Council:

a) Support the recommendations of the Commission and access of the Commission to the UN Security Council;

b) Transmit the report of the Commission to the UN Security Council through the Secretary-General.

170. To the UN General Assembly:

a) Support the work of the Commission, inviting it to provide regular updates;

b) Uphold the recommendations of the Commission and exert influence toward a peaceful solution for the country.

171. To the UN Security Council:

a) Support the work of the Commission and enable it to access the Security Council to provide periodic briefings on developments;

b) Facilitate and underpin a comprehensive peace process for the country, with the full participation of all stakeholders;

c) Commit to ensure the accountability of those responsible for violations including possible referral to international justice.

Annexes

Annex I

Correspondence |f|Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Notes:

*. Reproduced as submitted GE.12- [Back]

a. The commissioners are Paulo Sergio Pinheiro (Chairperson), Karen Koning AbuZayd, Vitit Muntarbhorn and Carla del Ponte. [Back]

b. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/IICISyria/Pages/IndependentInternationalCommission.as [Back]

c. UNHCR figures for refugees are 1,528,924: Iraq (148,028); Jordan (474,405); Lebanon (476,838); Turkey (350,736); Egypt (68,865); North Africa (10,052). [Back]

d. See AHRC 22/59, par. 42, for the commission's definition. [Back]

e. Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, which entered into force on 8 February 1928. [Back]

| This document has been published on 05Jun13 by the Equipo Nizkor and Derechos Human Rights. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. |