| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

| Information |  | |

Derechos | Equipo Nizkor

| ||

26Oct14

Aggregate Report on the Comprehensive Assessment

Contents 1.1 Comprehensive assessment

1.2 Outcomes of the comprehensive assessment

1.3 Structure of this report

1.4 Comprehensive assessment in numbers2 Nature of the comprehensive assessment

2.1 Rationale

2.2 Components

2.3 Execution

2.4 Characteristics of the comprehensive assessment3 Scope of the exercise and methodological overview

3.1 Participating banks

3.2 Overview of the methodology

3.3 Risks not addressed in the comprehensive assessment4.1 AQR quality assurance

4.2 Stress test and join-up quality assurance

4.3 Supervisory dialogue5 Aggregate outcomes of the comprehensive assessment

5.1 Projected capital change under the comprehensive assessment

5.2 Shortfall identified by the comprehensive assessment6.1 Harmonisation of asset quality metrics

6.2 AQR adjustments to asset carrying values

6.3 Remedial actions to be implemented by banks following the comprehensive assessment7 Stress test and join-up with AQR outcomes

7.1 Outcomes of the stress test

7.2 Quantitative findings of the stress test by key drivers8.1 Capital quantity

8.2 Capital composition9.1 List of participating banks in the comprehensive assessment and peer groups

9.2 Detailed results

9.3 List of acronyms and abbreviations

9.4 Bibliography

9.5 Geographic clusters used for analysis of collateral value adjustmentsList of figures

Figure 1 Gross AQR adjustment by country of participating bank Figure 2 Comprehensive assessment median projected adverse scenario reduction in capital ratio by country of participating bank Figure 3 Comprehensive assessment capital shortfall by main components Figure 4 Comprehensive assessment capital shortfall by country of participating bank Figure 5 Schematic of AQR work blocks Figure 6 Illustration of risk-based portfolio selection, credit RWA coverage Figure 7 Illustration of risk-based portfolio selection, number of portfolios Figure 8 Selected exposures by asset class Figure 9 Selected exposures by debtor geography Figure 10 GDP impact across CEBS/EBA EU-wide stress test exercises in the euro area, deviation between adverse and baseline Figure 11 AQR quality assurance model Figure 12 Overview of AQR quality assurance checks Figure 13 Quality assurance correction process Figure 14 Example where two or more impairment triggers hit and debtor remains performing, as percentage of total performing debtors pre- and post-QA Figure 15 Example of the impact of credit file review QA on the haircut applied to the large corporate aggregate market value of collateral in one Member State Figure 16 Comprehensive assessment adverse scenario impact on capital Figure 17 Comprehensive assessment adverse scenario impact on capital ratios Figure 18 Comprehensive assessment projected adverse scenario impact on capital by country of participating bank Figure 19 Development of CET1 ratio distribution by participating bank Figure 20 Comprehensive assessment shortfall by main components Figure 21 Capital shortfall by component of the comprehensive assessment by country of participating bank Figure 22 Capital shortfall by country of participating bank Figure 23 Capital shortfall grouped by bank stress test balance sheet type and RWA size group Figure 24 Capital shortfall bank distribution Figure 25 Bank internal NPE definition compared to key EBA ITS simplified NPE approach Figure 26 Bank classification of derivative and non-derivative holdings under the IFRS 13 fair value hierarchy Figure 27 Gross AQR adjustment by country of participating bank Figure 28 Impact of the AQR by component Figure 29 Summary of impact of provisions by asset class Figure 30 Impact of the credit file review by driver Figure 31 Number of reclassified NPEs by country of participating bank Figure 32 Change in provisions and coverage ratio by asset class for reclassified NPEs Figure 33 Change in provisions and coverage ratio by asset class for going and gone concern existing NPEs Figure 34 Pre- and post-AQR coverage ratio by asset class for going and gone concern existing NPEs Figure 35 Collateral valuation adjustments throughout the AQR Figure 36 Collateral value reduction for selected real estate property types Figure 37 Collateral value adjustment by location of real estate collateral Figure 38 Real estate collateral valuation adjustment by year of last appraisal Figure 39 Real estate valuation adjustment by reappraisal type (only reappraised properties) Figure 40 Provision increases for the shipping industry by country of participating bank Figure 41 Impact of projection of findings on non-retail provisioning Figure 42 Additional collective provisions by type of provision Figure 43 Additional specific retail provisions by asset class Figure 44 Additional specific provisions by debtor geography Figure 45 Additional IBNR by AQR asset class Figure 46 Additional IBNR by SSM debtor geography Figure 47 Impact of the AQR fair value exposures review by component Figure 48 AQR adjustment of revaluations grouped by RWA of participant bank Figure 49 AQR impact of the CVA review and main drivers Figure 50 AQR impact of the CVA review grouped by RWA of participating banks Figure 51 Models classified depending on outcome of the AQR review, and AQR impact of the derivative pricing model review, by type of issue Figure 52 Impact of the stress test on the aggregate CET1 capital by country under the adverse scenario in € billion and in percentage of RWA Figure 53 Aggregate stress test impact by risk driver under the baseline scenario Figure 54 Aggregate stress test impact by risk drivers under the adverse scenario Figure 55 Decomposition of loan losses across portfolios and banks under the baseline and adverse scenario Figure 56 Net interest income development across banks under the baseline and adverse scenario Figure 57 Net fee and commission income development across banks under the baseline and adverse scenario Figure 58 Sovereign losses on AFS and FVO portfolios across banks under the baseline and adverse scenario Figure 59 RWA development across banks under the baseline and adverse scenario Figure 60 Development of administrative and other operating expenses as an aggregate across banks under the baseline scenario Figure 61 Distribution of changes to CET1 ratios across banks following a static vs. dynamic balance sheet assumption under the baseline and adverse scenarios Figure 62 Join-up impact by bank in relation to AQR adjustments Figure 63 Total absolute and relative impact of join-up by country of participating bank under the adverse scenario Figure 64 CET1 impact of join-up by type (credit vs. other effects) under the baseline scenario Figure 65 CET1 impact of join-up by type (credit vs. other effects) under the adverse scenario Figure 66 Cumulative aggregated equity increase 2008-2013 Figure 67 Breakdown of capital actions undertaken by significant banks in 2014 Figure 68 CET1 issuance by country of participating bank, including issuances between 1 January and 30 September 2014 Figure 69 Aggregated capital actions undertaken by participating banks in 2014 Figure 70 Capital actions by participating bank, 1 January to 30 September 2014 Figure 71 Impact of capital actions on the aggregated capital shortfall Figure 72 Bank-level leverage ratios by country of participating banks Figure 73 Leverage ratio bank distribution Figure 74 Total transitional adjustments by country of participating banks as of 1 January 2014 Figure 75 Bank-level impact of transitional adjustments to CET1 Figure 76 Stock of DTAs requiring future profitability, pre-AQR List of tables

Table 1 Participating banks with a shortfall Table 2 Balance sheet used for the stress test Table 3 Impact of application of EBA ITS simplified NPE approach and the credit file review by AQR asset class Table 4 Summary of AQR adjustment by component Table 5 Distribution of impairment triggers for reclassified NPEs Table 6 Illustration of provisioning impact of the projection of findings split by portfolio type Table 7 AQR impact of revaluations by asset class (total value examined in portfolio samples) Table 8 Total impact by stress test component Table 9 Phase-in percentages applicable to the majority of CET1 deductions Table 10 Phase-in percentages applicable to the deduction of DTAs that rely on future profitability and existed prior to 1 January 2014 Table 11 List of participating banks in the comprehensive assessment and inclusion in peer groups Table 12 CET1 ratios for participating banks (%) Table 13 Buffer (+) / shortfalls (-) for participating banks (€ billion) Table 14 AQR adjustment by bank and asset class (€ million)

The ECB conducted the comprehensive assessment to prepare for assuming banking supervision tasks in November 2014. This resulted in aggregate adjustments of €48 billion to participating banks' asset carrying values which will be reflected in their accounts or in supervisory capital requirements. Overall, the exercise has identified capital shortfalls for 25 banks, totalling €25 billion. After accounting for equity already raised this year as well as agreed restructuring plans, shortfalls remain at 12 banks. Banks will be required to fill these shortfalls within six to nine months.

The European Central Bank (ECB) will assume banking supervision tasks in November 2014 in its role within the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). In preparation, the ECB has conducted a comprehensive assessment of 130 |1| banks. The stated objectives of this exercise were to:

- Strengthen banks' balance sheets by repairing the problems identified through the necessary remedial actions.

- Enhance transparency by improving the quality of information available on the condition of the banks.

- Build confidence by assuring all stakeholders that, on completion of the identified remedial actions, banks will be soundly capitalised.

This report provides an overview of the approach taken and presents the results of the exercise.

The comprehensive assessment was broad in scope. The 130 credit institutions included in the exercise (i.e. "the participating banks" |2|) had total assets of €22.0 trillion, which accounts for 81.6% of total banking assets in the SSM. |3|

The comprehensive assessment consisted of two components.

1) The asset quality review (AQR) was a point-in-time assessment of the accuracy of the carrying value of banks' assets as of 31 December 2013 and provided a starting point for the stress test. The AQR was undertaken by the ECB and national competent authorities (NCAs), and was based on a uniform methodology and harmonised definitions. The scale of the exercise was unprecedented; it provided a thorough health check of the banks that will be subject to direct supervision by the ECB.

The exercise was based on the Capital Requirements Regulation and Directive (CRR/CRD IV), on the definition of regulatory capital as of 1 January 2014. Under the AQR, banks were required to have a minimum Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio of 8%.

2) The stress test provided a forward-looking examination of the resilience of banks' solvency to two hypothetical scenarios, also reflecting new information arising from the AQR. The stress test was undertaken by the participating banks, the ECB, and NCAs, in cooperation with the European Banking Authority (EBA), which also designed the methodology along with the ECB and the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB). Under the baseline scenario, banks were required to maintain a minimum CET1 ratio of 8%; under the adverse scenario, they were required to maintain a minimum CET1 ratio of 5.5%.

The AQR respected current accounting and prudential regulation, including the CRR/CRD IV capital rules. |4| In some areas the ECB's methodology involved additional prudential prescription to accounting concepts in order to achieve consistency and adequate conservatism. The results are of a prudential nature. AQR-adjustments were made, often in cases where banks were not breaching accounting rules. However, it is expected that many banks will likely choose to reflect many of these changes in their accounts. Examples of areas in which additional prescription was provided include impairment triggers, the calculation of individual specific provisions, and collateral valuations.

The stress test is not a forecast of future events, but a prudential exercise to address banks' ability to withstand weaker economic conditions. In the stress test, banks' projections were subject to centrally defined requirements in order to ensure appropriate conservatism and high-quality output. For example, balance sheets were assumed to remain constant over the stress test horizon in terms of total exposure volume, maturity and product mix (i.e. the static balance sheet assumption). |5|

Within both components, the approach taken aimed for a rigorous and consistent exercise, emphasising a "level playing field" between banks.

Within the AQR, a detailed asset-level review was performed for over 800 specific portfolios making up 57% of the banks' risk-weighted assets. This resulted in the detailed analysis of more than 119,000 borrowers; the assessment of the valuation of about 170,000 collateral items; the building of 765 models to "challenge" the banks' own estimates of collectively assessed provisions and over 100 models to assess their CVA calculation; the revaluation of over 5,000 of the most complex fair value exposures; and the review of over 100 complex valuation models. This in-depth review employed over 6,000 experts at its height.

In order to maintain consistency and equal treatment across both the AQR and stress test, central ECB teams independently performed quality assurance on the work of the banks and NCAs. The ECB was in close contact with NCAs, responding to over 8,000 methodology and process questions. The ECB reviewed and challenged outcomes from an SSM-wide perspective using comparative benchmarking, as well as engaged with NCAs to investigate specific issues that arose. Over 100 experts from the ECB along with external support professionals were involved in this quality assurance activity.

1.2 OUTCOMES OF THE COMPREHENSIVE ASSESSMENT

The AQR resulted in aggregate adjustments of €47.5 billion to participating banks' asset carrying values as of 31 December 2013. These adjustments originated primarily from accrual accounted assets, particularly adjustments to specific provisions on non-retail exposures. Additionally, non-performing exposure (NPE) stocks were increased by €135.9 billion across the in-scope institutions, as NPE definitions were moved onto a harmonised and comparable basis, including the examination of forbearance as a trigger of NPE status.

The prudential and accounting implications will be assessed by the SSM's new Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs) along with the qualitative conclusions of the exercise regarding, for example, the soundness of banks' internal processes. This will mean that even where banks do not reflect adjustments in their accounts all conclusions will be captured in ongoing supervision and in supervisory capital requirements. As Figure 1 shows, the AQR adjustments differ by jurisdiction as consistent standards have been applied where previous approaches may have diverged.

Figure 1 Gross AQR adjustment by country of participating bank

Click to enlargeIn addition to adjustments made directly to current carrying values, the AQR result was also reflected in the projection of banks' capital adequacy under hypothetical scenarios performed in the stress test.

Under the adverse scenario, the banks' aggregate available capital is projected to be depleted by €215.5 billion (22% of capital held by participating banks) and risk weighted assets (RWA) to increase by about €860 billion by 2016; including this as a capital requirement at the threshold level brings the total capital impact to €262.7 billion in the adverse scenario.

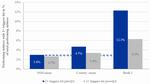

This capital impact leads to a decrease of the CET1 ratio for the median participating bank by 4.0 percentage points from 12.4% to 8.3% in 2016. The reduction in the median CET1 ratio projected for banks in each country is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Comprehensive assessment median projected adverse scenario reduction in capital ratio by country of participating bank

Click to enlargeAlthough not fully comparable, the median projected CET1 ratio reduction in the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) carried out in the United States in 2014 was 2.9% |6| ; it was 3.9% in the AQR and stress test carried out in Spain in 2012 |7| , and 2.1% in the EBA stress test carried out in 2011 |8| .

Overall, the comprehensive assessment identified a capital shortfall of €24.6 billion across 25 participating banks after comparing these projected solvency ratios against the thresholds defined for the exercise. |9|

The €24.6 billion shortfall can be disaggregated into three components. The amount of shortfall that arose from the stress test conducted by the banks and quality assured by the ECB was €11.2 billion before making any adjustments due to AQR results and after accounting for all existing capital buffers as of 31 December 2013. The inclusion of the reduction in starting-point available capital due to AQR adjustments increases this shortfall to €21.9 billion. Finally, the reflection of the new information on asset performance learned through the AQR in the stress test projections resulted in the full shortfall of €24.6 billion. These impacts are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Comprehensive assessment capital shortfall by main components

Click to enlargeThe overall comprehensive assessment shortfall is shown again in Figure 4, split by country of participating bank. It is presented in terms of country-level RWA, i.e. reflecting the significance of the shortfall relative to the size of the banks included in the exercise and showing the direct impact on banks' CET1 ratio.

Figure 4 Comprehensive assessment capital shortfall by country of participating bank

Click to enlargeThis capital shortfall identified by the comprehensive assessment can be placed in the context of capital recently raised by the participating banks. Between the onset of the financial crisis in 2008 and 31 December 2013, capital in excess of €200 billion has been raised by banks participating in the exercise. Since 1 January 2014, a further €57.1 billion has been raised which is not counted in the results above, but which will be considered as mitigation of the shortfalls found.

On a bank level, the capital needs identified are presented below, along with the capital raised by each institution since 31 December 2013 |10| and the remaining capital shortfall. For each of the 25 institutions identified in Table 1, a capital plan will be submitted to the respective JST within two weeks of the publication of this document, detailing how the capital shortfall will be filled. The JSTs will check that any such plans are sound and include the capital raising already undertaken by the participating banks with shortfalls. |11|

When all of the capital that has been raised already (net of capital instrument buyback) is offset against the shortfalls, €9.5 billion |12| remain to be filled, distributed across 13 banks. Two banks within this list that have a shortfall on a static balance sheet projection |13| will have dynamic balance sheet projections (which have been performed alongside the static balance sheet assessment as restructuring plans were agreed with DG-COMP after 1 January 2014) taken into account by the JSTs in determining their final capital requirements. Under the dynamic balance sheet assumption, one bank has no shortfall and one bank has practically no shortfall.

Table 1 Participating banks with a shortfall Bank Name CET1 ratio starting point CET1 ratio post AQR CET1 ratio baseline scenario CET1 ratio adverse scenario Capital shortfall (€ billion) Net eligible capital raised (€ billion) Capital shortfall post net capital raised (€ billion) Eurobank |1| 10.6% 7.8% 2.0% -6.4% 4.63 2.86 1.76 Monte dei Paschi di Siena 10.2% 7.0% 6.0% -0.1% 4.25 2.14 2.11 National Bank of Greecei 10.7% 7.5% 5.7% -0.4% 3.43 2.50 0.93 Banca Carige 5.2% 3.9% 2.3% -2.4% 1.83 1.02 0.81 Cooperative Central Bank -3.7% -3.7% -3.2% -8.0% 1.17 1.50 0.00 Banco Comercial Portugues 12.2% 10.3% 8.8% 3.0% 1.14 -0.01 1.15 Bank of Cyprus 10.4% 7.3% 7.7% 1.5% 0.92 1.00 0.00 Oesterreichischer Volksbanken-Verbund 11.5% 10.3% 7.2% 2.1% 0.86 0.00 0.86 permanent tsb 13.1% 12.8% 8.8% 1.0% 0.85 0.00 0.85 Veneto Banca 7.3% 5.7% 5.8% 2.7% 0.71 0.74 0.00 Banco Popolare 10.1% 7.9% 6.7% 4.7% 0.69 1.76 0.00 Banca Popolare di Milano 7.3% 6.9% 6.5% 4.0% 0.68 0.52 0.17 Banca Popolare di Vicenza 9.4% 7.6% 7.5% 3.2% 0.68 0.46 0.22 Piraeus Bank 13.7% 10.0% 9.0% 4.4% 0.66 1.00 0.00 Credito Valtellinese 8.8% 7.5% 6.9% 3.5% 0.38 0.42 0.00 Dexia |2| 16.4% 15.8% 10.8% 5.0% 0.34 0.00 0.34 Banca Popolare di Sondrio 8.2% 7.4% 7.2% 4.2% 0.32 0.34 0.00 Hellenic Bank 7.6% 5.2% 6.2% -0.5% 0.28 0.10 0.18 Munchener Hypothekenbank 6.9% 6.9% 5.8% 2.9% 0.23 0.41 0.00 AXA Bank Europe 15.2% 14.7% 12.7% 3.4% 0.20 0.20 0.00 C.R.H. - Caisse de Refinancement de l'Habitat 5.7% 5.7% 5.7% 5.5% 0.13 0.25 0.00 Banca Popolare dell'Emilia Romagna 9.2% 8.4% 8.3% 5.2% 0.13 0.76 0.00 Nova Ljubljanska banka |3| 16.1% 14.6% 12.8% 5.0% 0.03 0.00 0.03 Liberbank 8.7% 7.8% 8.5% 5.6% 0.03 0.64 0.00 Nova Kreditna Banka Maribor|3| 19.6% 15.7% 12.8% 4.4% 0.03 0.00 0.03 Total 10.0% 8.4% 7.2% 2.1% 24.62 18.59 9.47 1. These banks have a shortfall on a static balance sheet projection, but will have dynamic balance sheet projections (which have been performed alongside the static balance sheet assessment as restructuring plans were agreed with DG-COMP after 1 January 2014) taken into account in determining their final capital requirements. Under the dynamic balance sheet assumption, these banks have no or practically no shortfall taking into account net capital already raised.

2. Taking into account the orderly resolution plan of this institution, which benefits from a State guarantee, there is no need to proceed with capital raising following comprehensive assessment results.

3. The impact on 2014 of the restructuring measures already taken to improve structural profitability and the maintenance of retained earnings in banks will cover the shortfalls identified.

The calculation of CET1 used within the comprehensive assessment and reflected above has been performed based on the existing legal requirements and national transitional arrangements, with the notable exception of the removal of the prudential filter on unrealised gains and losses on sovereign exposures in available-for-sale (AFS), for which an EBA-defined harmonised phase-in has been applied. |14| These national discretions over transitional arrangements introduce variation in the current definition of capital used across banks and countries. The resulting divergences will gradually diminish over the coming years as transitional arrangements are phased out. In the meantime, the ECB recognises the need to improve the consistency of the definition of capital and the related quality of CET1 capital. This will be an issue for the SSM to address as a matter of priority. The disclosure of the impact of the transitional provisions on CET1 allows for an objective comparison, where the impact of the national options is neutralised.

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Context of the exercise: objectives, guiding principles and how to interpret results.

- Scope of the exercise and methodological overview: the banks subject to the exercise; what it does and does not aim to address; a high-level view of its approach.

- Quality assurance: process and analysis performed to ensure consistent and accurate results.

- Aggregate outcomes of the comprehensive assessment.

- Outcomes of the AQR and further analysis: review of the detailed drivers of the AQR results.

- Outcomes of the stress test and further analysis: review of the detailed drivers of the stress test results.

- Capital measures taken by participating banks: capital quantity and composition of participating banks' capital, including the treatment of the deductions and the related quality of CET1 capital.

1.4 COMPREHENSIVE ASSESSMENT IN NUMBERS

The exercise was comprehensive in scope:

- 19 participating countries.

- 130 participating banks.

- 81.6% of total SSM banking assets covered.

- More than 6,000 experts involved in ECB and NCA bank teams.

The exercise was comprehensive in nature:

- Over 800 individual portfolios examined.

- Over 119,000 debtors analysed in detail.

- Over 170,000 collateral items revalued.

- Over 850 provisioning and CVA models challenged.

- Over 5,000 securities revalued.

2 NATURE OF THE COMPREHENSIVE ASSESSMENT

This chapter explains the rationale for the comprehensive assessment, its components, describes how it was executed and finally introduces some key features of the exercise that the reader should be aware of when interpreting the results.

In October 2013, the ECB announced that it would conduct a comprehensive assessment of the euro area banking system in conjunction with participating national competent authorities (NCAs) responsible for banking supervision |15|, to be completed prior to the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) assuming its supervisory responsibilities and duties for the significant euro area banks on 4 November 2014. |16| This was required by Article 33(4) of the Council Regulation (EU) No 1024/2013 (SSM Regulation) which entered into force in early November 2013.

The comprehensive assessment represents a key step forward for the SSM by providing a consistent and objective assessment of the health of banks' balance sheets and their solvency prior to the handover of responsibility. More generally, the goal of the exercise is to help prevent further burdens on taxpayers by strengthening the resilience of the financial sector to future crises. Furthermore, the exercise aims to facilitate banks' provision of credit to the European economy by reducing the uncertainty over their solvency. To this end, the objectives of the comprehensive assessment are threefold:

1. Repair - identifying and implementing any necessary remedial actions that are required to safeguard solvency in the near term.

2. Transparency - enhancing the quality of information available on the condition of banks to facilitate a more accurate assessment of their solvency.

3. Confidence building - assuring stakeholders that banks will be fundamentally sound and trustworthy after the identified remedial actions are implemented.

This report, in association with the detailed bank level results disclosed separately, aims to inform the reader of the process, governance and results of the comprehensive assessment.

The exercise comprised two pillars, namely the asset quality review (AQR) and the stress test.

The AQR aimed to review the carrying value of assets on the participating banks' balance sheets as of 31 December 2013. The end result was an indication of the need for additional provisions for losses on exposures on banks' balance sheets, leading to prudently calculated AQR-adjusted capital ratios, which allowed for the meaningful comparison of all participating banks on a like-for-like basis.

Based on the AQR-adjusted balance sheet, the stress test examined the resilience of banks against two separate scenarios - a baseline and adverse scenario - starting in 2014 and running to the end of 2016. Under both scenarios, the solvency ratio of each bank was analysed over that period to understand bank sensitivities given prescribed stressed economic conditions. The baseline scenario was provided by the European Commission and reflected then-prevailing official macroeconomic forecasts while the adverse scenario represented a severe economic downturn triggered by a materialisation of the main economic risks identified by the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB).

A number of parties were involved in the execution of the comprehensive assessment.

- Participating banks were responsible for fulfilling their obligations to the NCA, providing data and running the stress test.

- NCAs were responsible for all national project management activities, making sure that the banks fulfilled their responsibilities, performing initial quality assurance and reporting to the ECB. The NCAs appointed NCA bank teams comprising NCA staff and external auditors, property appraisers and valuation advisers who provided a third party perspective. This composition for the NCA bank teams brought expertise and independence, given that neither the bank's statutory auditor nor its day-to-day supervisor were involved in the completion of that bank's AQR.

- At the ECB, the comprehensive assessment was conducted under the lead of a project manager, who oversaw the execution of the entire exercise in cooperation with the heads of national steering committees. In carrying out his tasks, he was assisted by a Central Project Management Office (CPMO) and a joint stress testing quality assurance structure that was established in cooperation with the Directorate General Macro-Prudential Policy and Financial Stability. The CPMO was the central coordination point for the exercise; it monitored the progress by NCAs and their constituent banks and executed the final quality assurance on the asset quality review (with the specific support of seven country teams - see Section 4.1.1). The stress testing governance structure was composed of a horizontal review unit and a central country review unit divided into various country teams. The former was tasked with conducting quantitative data checks and running the top-down stress test tool, including sensitivity analyses. The latter conducted an in-depth analysis of bottom-up stress test results and communicated with NCAs. The ECB was assisted by an external consultant in the design of the AQR and stress test methodology and the conduct of the comprehensive assessment as a whole.

- Supervisors outside of the SSM assisted the ECB in the completion of the exercise for any subsidiaries of SSM banks located outside of the SSM which qualified for inclusion in the comprehensive assessment.

- The ECB worked closely with the EBA to complete the stress test pillar of the comprehensive assessment.

The two components of the comprehensive assessment were executed by these bodies in different ways, reflecting the nature of each exercise.

- The AQR was executed by the NCA bank teams, following a methodology designed and published by the ECB. |17| Results were submitted by the NCA bank teams to the NCAs which reviewed the work of their NCA bank teams and submitted them to the ECB for consideration and collation. Central quality assurance was performed and requests made by the ECB of NCAs and the NCA bank teams to investigate certain results - further details of this process can be found in Section 4.1. Both the ECB and NCAs were supported by external advisors (including auditors, consultants and appraisers) who brought expertise and independence to the review.

- The stress test was executed by the banks themselves, following a methodology designed and published by the EBA along with a baseline scenario founded on the European Commission's Winter 2014 forecast and an adverse scenario developed by the ESRB in cooperation with the NCAs, the EBA and the ECB. Results were submitted for review to each bank's respective NCA, and then to the ECB. Therefore, although the ECB retained the final versions, the results were in all cases initially created by the bank. The banks' stress test submissions were subject to a thorough quality assurance process by NCAs and the ECB. In cases where their stress test outcomes were not considered appropriate in view of the EBA methodology and judged against ECB benchmarks |18|, banks were requested to adjust and resubmit their results. Finally, the AQR and stress test were integrated through the "join-up" process (outlined in Section 3.2), centrally executed by the ECB in accordance with the published methodology. The tool used to perform the join-up calculation was shared with both the banks and NCAs; the NCAs and ECB independently calculated the result in parallel and discussed the outcome in order to corroborate the final result.

- Following completion and finalisation of the joined-up comprehensive assessment result, a "supervisory dialogue" process was conducted between the participating banks and their Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs). During the supervisory dialogue meetings, partial and preliminary results of the comprehensive assessment were shared and discussed. The banks were given 48 hours following the meeting to provide comments and questions to the ECB. The banks were also required to resubmit their final stress test templates within 96 hours following the supervisory dialogue meetings if any further adjustments were deemed necessary. Further information is in Section 4.3.

- After disclosure of the results of the comprehensive assessment, the capital actions required of the banks will be assessed and monitored by the respective JSTs. Banks identified as having capital shortfalls will be required to take remedial actions and to submit capital plans within two weeks of the public disclosure of the results detailing how the shortfalls will be covered. Capital plans must show how any shortfalls will be addressed within six months for those identified in the AQR or the baseline stress test scenario, and within nine months for those identified in the adverse stress test scenario. Further information on this is given in Chapter 8.

- The JSTs will also define the process for, and track the incorporation of, remedial actions required of each bank, as well as the findings that need to be reflected in forthcoming accounts following the comprehensive assessment in line with the applicable accounting frameworks.

- The 2014 Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) will be used to further embed the results of the comprehensive assessment, with these results forming an input to the capital adequacy assessment alongside the national SREP and existing capital plans. As a result of this process, significant credit institutions (the banks under direct supervision by the ECB in the SSM |19|) that have a shortfall in the comprehensive assessment will have the outcome of the comprehensive assessment as a floor for the SREP capital decision.

2.4 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE COMPREHENSIVE ASSESSMENT

A number of characteristics of the comprehensive assessment should be borne in mind when considering the results.

The comprehensive assessment was a prudential rather than accounting exercise. Although current accounting (IFRS or national GAAP) and prudential rules were considered as binding and were observed strictly, the outcomes of the comprehensive assessment will not necessarily be reflected directly in banks' accounts following the exercise.

In some cases where more than one approach was consistent with accounting rules the comprehensive assessment prescribed a favoured approach following prudential and economic logic. Hence a number of situations in which AQR-adjustments have been made do not indicate that the original bank accounts failed to meet with accounting standards.

The comprehensive assessment sought to maintain a level playing field across the 130 participating banks by providing guidance on a range of important inputs such as non-performing exposure (NPE) definition, impairment triggers, provisioning approaches for going concern NPEs, collateral valuation, point-in-time collective provisioning, and credit valuation adjustment (CVA) calculation where possible. Such guidance was not, however, possible in all areas. The emphasis on objective data and indicators based on data in the AQR allowed for a more consistent approach across countries and banks; the AQR represents a substantial step forward in harmonising such definitions in the euro area.

NCAs were aided in this by the published methodology |20| which included numerous "ECB thresholds", supplemented by a central frequently asked questions (FAQ) and helpdesk process, as well as the thorough review of any outliers or anomalies during the central quality assurance process. These ECB thresholds provided additional prescription to practices in a number of areas in which accounting standards allow a range of approaches but did not contradict those standards. These ECB thresholds are not expected to be used for accounting purposes following the comprehensive assessment, and where their application has led to AQR-adjustments it is the responsibility of participating banks to assess whether those adjustments have to be reflected in their statutory accounts. That said, the comprehensive assessment will form the basis for extensive follow-up work beyond addressing capital shortfalls.

Nevertheless, a number of findings from the AQR do stem directly from adjustments in which the previous practice of participating banks was explicitly non-compliant with accounting practice. |21| Participating banks are expected to assess these issues and reflect accounting breaches in their accounts. This process will be monitored by the Joint Supervisory Teams of the banks in question.

The comprehensive assessment involved central oversight in both methodology definition and quality assurance for consistency and transparency. Not only was a substantial methodological manual and body of additional clarifying support provided, but all significant departures from the prescribed methodology (e.g. in response to material country/bank specific circumstances) required written approval from the ECB which was only granted in exceptional circumstances. Central quality assurance was enabled by gathering large quantities of data across all countries and banks during the execution of the AQR, and by collecting and assessing the results of the stress tests performed by the banks themselves. Where data reflected divergent approaches, the ECB checked that the methodology was being adhered to, although specific circumstances were taken into account where appropriate. Further details of the quality assurance approach can be found in Chapter 4.

The AQR was conducted using a general principle that an approach would be adopted only where objective data was available to justify it. Whenever such data was not available a generally conservative fall-back assumption was used and applied consistently across the SSM. An example of this is the use of loss emergence periods in the collective provisioning work block. Loss emergence periods have a direct impact in provisions required for performing loans. A rebuttable supposition of 12 months was employed, which could only be lowered where granular, objective data was analysed by the NCA bank team and approved by the ECB to show that a shorter period was appropriate.

The AQR was a targeted, risk-based exercise. The results therefore cannot be extrapolated to portfolios that were not selected for review. With 130 banks in-scope, covering more than €22.0 trillion of assets and €16.4 trillion of loans |22|, a file-by-file review of all exposures was not possible within the AQR. Nevertheless, all portfolios of the participating banks were considered for inclusion, on a consistent set of metrics, during the first phase of the AQR. The final portfolio selection was performed by both the ECB and the respective NCA and aimed to cover those portfolios with the highest chance of material misstatements. The selection was designed so that the majority of credit risk-weighted assets (cRWA) |23| and the majority of material portfolios |24| by count were covered in detail. Because the selection was risk-based in this way, it was likely to constitute a biased sample of portfolio misstatement levels and therefore it would be inaccurate to extrapolate findings to un-selected portfolios. Following sampling, more than 119,000 debtors were analysed with millions of data items collected during the credit file review and about 170,000 collateral items valued, allowing the ECB to perform granular analyses. Furthermore, 765 collective provisioning challenger models and over 100 CVA challenger models were built, 5,000 level 3 cash positions re-valued and over 100 complex valuation models reviewed.

The stress test is a forward-looking exercise that provides insight into the ability of a bank to withstand pre-defined adverse economic conditions. It should be noted that the stress test is not a forecast of future events, but rather a prudential gauge of participating banks' resilience under severe but plausible macro-economic conditions. For example, a number of restrictive rules were imposed by the stress test methodology that constrict the responses of the participating banks to stress (such as the static balance sheet assumption, which for example does not allow the banks to deleverage as they may otherwise in an adverse scenario). These rules enhance the prudential nature of the exercise. The stress test was performed in close cooperation with the EBA. The EBA published the stress test methodology, scenarios and disclosure templates which were used by the ECB when performing the stress test pillar of the ECB's comprehensive assessment.

3 SCOPE OF THE EXERCISE AND METHODOLOGICAL OVERVIEW

The purpose of this chapter is to outline the scope of the comprehensive assessment, namely the 130 banks identified by the ECB to be reviewed and the risks to be covered in the AQR and stress test. The chapter also provides a brief methodological overview of the AQR and stress test as a summary of the detailed methodological documents released by the ECB and, in the case of the stress test, the EBA. |25|

The ECB has undertaken a comprehensive assessment of 130 credit institutions, financial holding companies or mixed financial holding companies with total assets of €22.0 trillion at the end of 2013, accounting for 81.6% of total banking assets in the SSM. These banks were identified based on significance criteria referred to in Article 6(4) of the SSM Regulation. In general, a bank in an SSM Member State was included if any of the following criteria applied:

- The total value of the bank's assets exceeds €30 billion.

- The ratio of the bank's total assets to GDP of its country of establishment exceeds 20%, unless the total value of their assets is below €5 billion.

- The institution is among the three largest credit institutions in a participating SSM Member State, regardless of size.

In addition to the simple application of these criteria, the ECB also took into account changes that might have occurred between the start of the exercise and the commencement of supervision; by applying a 10% margin of deviation to the above thresholds, it included borderline banks in the comprehensive assessment. A full list of in-scope banks and banks due to be subject to SSM Regulation can be found in Appendix 9.1.

A key requirement of the comprehensive assessment was that it considered the "highest level of consolidation in participating Member States" in the assessment of whether banks met the above criteria. Numerous banking groups included in the list have established subsidiaries in other participating Member States that would themselves meet the criteria on a sub-consolidated or solo basis. The latter are not listed separately unless they are among the three largest credit institutions in a participating Member State. In all cases the comprehensive assessment was carried out at the highest level of consolidation of the entity subject to the review as listed in the Appendix. |26|

Each of the 130 banks subject to the comprehensive assessment was examined within the AQR. A subset of 76 banks was included in the AQR's fair value exposure review, a detailed examination of mis-valuation risk within the most complex fair valued instruments. This list was determined using absolute and relative criteria such as the overall size of the trading book, the size of level 3 fair value financial instrument positions (including those in the banking book) and other relevant risk metrics.

All participating banks were included in the stress test exercise conducted in cooperation with the EBA. |27| The 130 participating banks can be separated into three groups with respect to the balance sheet assumption used in the stress test.

- Non-restructuring banks: the EBA methodology prescribes that the stress test was performed under a static balance sheet assumption, in the absence of an agreed restructuring plan with the European Commission. This required banks to apply a zero growth rate of the total balance sheet and unchanged business mix across the time horizon of the exercise. |28|

- Restructuring banks (approved before 31 December 2013): banks which are currently implementing a restructuring plan approved by the European Commission (Directorate General of Competition, DG COMP) that was agreed before 31 December 2013 were allowed to apply a dynamic balance sheet assumption. Implementation of a dynamic balance sheet reflects the implementation of the material changes to the business model of the bank that typically includes some mix of asset disposal, organic deleveraging, and risk reduction.

- Restructuring Banks (approved after 31 December 2013): banks which received DG-COMP's approval for a restructuring plan in the course of 2014 were required to produce stress test templates under the static balance sheet assumption. These banks were also allowed to prepare separate templates under the dynamic balance sheet assumption, and the results of the dynamic balance sheet assumption are also presented in the ECB disclosure template.

Table 2 Balance sheet used for the stress test Number of banks Disclosure of stress test results Supervisory response Static balance sheet 101 banks Stress test results are disclosed based on the static balance sheet assumptions. Supervisory response based on the lowest CET1 under the static balance sheet assumptions. Dynamic balance sheet 24 banks Stress test results are disclosed based on the dynamic balance sheet assumptions. Supervisory response based on the lowest CET1 under the dynamic balance sheet assumptions. Static and dynamic balance sheet assumptions 5 banks - in the case of Alpha Bank, Eurobank Ergasias, National Bank of Greece, Piraeus Bank in Greece, and Allied Irish Banks in Ireland, the results of the static balance sheet review are considered and reported. However, due to the acceptance of restructuring plans after 31 December 2013, an extra tab in the disclosure template will show the results of a dynamic balance sheet review. Stress test results are disclosed based on the static balance sheet assumption. The impact of the dynamic balance sheet assumptions are separately shown in the disclosure templates. Though the capital shortfall is based on the static balance sheet, the impact of restructuring/ the dynamic balance sheet will be taken into account in the supervisory response. 3.1.1 ADDITIONS AND WITHDRAWALS

The 130 banks in-scope for the comprehensive assessment differs from the originally selected 128 institutions |29| in the following ways.

- Three Lithuanian institutions were included in the final sample (AB DNB Bankas, AB SEB Bankas, Swedbank AB) in order to allow them to join the SSM once Lithuania adopts the euro from 1 January 2015.

- Banco Espirito Santo (Portugal) was removed from the selected institutions due to its resolution by the Banco de Portugal. It has not been possible to include the results of the comprehensive assessment for the successor institution, Novo Banco (Portugal), due to inability to conduct the exercise on time.

- Unicaja completed the acquisition of CEISS during the comprehensive assessment, and therefore one integrated disclosure template has been published for the new entity.

- Two disclosure templates for Wustenrot & Wurttembergische AG have been released for the two banking entities of the group, Wustenrot Bank AG Pfandbriefbank and Wustenrot Bausparkasse AG.

- It should also be noted that the 130 banks that performed the comprehensive assessment are not the same as the "significant credit institutions" that will be supervised directly by the ECB when it assumes supervisory responsibility. A number of banks reviewed during the comprehensive assessment have been classified as "less significant" institutions; these will continue to be directly supervised by the national competent authorities, while the ECB will exercise its indirect supervisory function. |30|

3.2 OVERVIEW OF THE METHODOLOGY

The ECB published the methodology for Phase 2 of the AQR on 11 March 2014. The EBA published the common methodology and scenario for the stress test on 29 April 2014, and following this on 8 August 2014 the ECB published guidance for the stress test quality assurance and join-up exercise. |31| Summaries of these methodologies follow below.

3.2.1 AQR METHODOLOGY

The AQR was composed of two phases. Phase 1 involved the process of portfolio selection; Phase 2 comprised nine interlinking work blocks with the final output of an AQR-adjusted CET1 ratio to be compared to the threshold of 8%.

Figure 5 Schematic of AQR work blocks

Click to enlargePhase 1

0. Portfolio selection: this was designed to focus the detailed analysis of the AQR on those portfolios most likely to have a material misstatement on a bank's balance sheets. The risk-based approach identified portfolios where the AQR adjustments could have a material impact on CET1. For each bank, at least 50% of credit RWA (cRWA) and "half of the material portfolios |32|" were selected to be analysed through the in-depth approach in Phase 2. Further detail on the process of portfolio selection is provided below.

Phase 2

1. Processes, policies and accounting review (PP&A): bank processes, policies and accounting practices have a key impact on the carrying values of assets in banks' balance sheets and, hence, were reviewed. Key topics covered included: application of fair value hierarchy; accounting classifications (e.g. as available-for-sale); high level qualitative approach to the CVA calculation; provisioning approach; treatment of NPEs and forbearance. |33|

2. Loan tape creation and data integrity validation (DIV): the credit analysis (sample selection and collective provisioning challenger model creation) was based on a "loan tape" provided by the bank. This loan tape included basic account information such as segment classification, missed payments status and identifiers of the loan/entity. The data was required to be of sufficient quality to perform the required analysis, which necessitated automated checks of the data set and a review of consistency across internal IT systems.

3. Sampling: given the volume of analysis involved it was not viable to review all exposures in every portfolio within the scope of the credit file review. Therefore, risk-based sampling was conducted in a manner that meant the sample chosen was both large enough, and representative enough, to allow for robust analysis and later projection back to cover the entire portfolio. The size of the sample depended on: the homogeneity of the portfolio, the risk of the portfolio, the total number of debtors and the level of debtor concentration. Samples were generally in the range of up to 20% of total exposure in a portfolio depending upon size and concentration. The approach to sampling was consistent with best practice as defined by adherence to ISA 530.

4. Credit file review (CFR): the credit file review involved NCA bank teams working on an exposure by exposure basis to verify that each credit exposure had been correctly classified in the bank's systems (e.g. correct regulatory segment, NPE status, impairment status) and that, if a specific provision was required, it had been set at an appropriate level. The CFR covered all loans, advances, financial leases and other off balance sheet items including specialised asset finance such as shipping and project finance.

5. Collateral and real estate valuation: a key input to determining appropriate carrying amounts is the valuation of collateral. Generally, the majority of collateral which did not have a third-party valuation conducted after 1 January 2013 was re-valued for all debtors selected in the sampling. The results of these valuations were used as inputs to the credit file review and collateral valuation components. To ease the burden of reappraisals, some use of valuations by independent internal units were allowed in particular circumstances described in detail in the AQR Manual.

6. Projection of findings of credit file review: findings of the credit file review were then projected to the unsampled part of the portfolio. Specifically, projected metrics were mainly impairment provisions and NPE reclassifications. |34| Projection of findings was applied to homogeneous pools of exposure within each portfolio called "strata" (in line with audit guidelines); portfolios were stratified based on the riskiness and exposure size of debtors. In order to prevent overstating the projection of single credit file review findings, a number of safeguards were implemented in the projection methodology (e.g. flagging of anomalies, common risk stratum based projection - using results from the whole risk bucket rather than just from the stratum, and overrides - in rare cases where results from the sample were felt to be unrepresentative which had to be approved centrally by the ECB).

7. Collective provisioning analysis: smaller, homogeneous, impaired exposures are typically provisioned using a collective provisioning approach - that is, a point-in-time statistical model of incurred loss. Similarly, incurred but not reported (IBNR |35|) and other general provisions are usually set using collective models. Therefore in order to verify that provisioning levels were appropriate it was critical that collective provisioning models were fully aligned with the letter and spirit of accounting rules (IAS |36| 39 or nGAAP |37|). This was performed using a comparison of banks' practices to provisioning levels suggested by a unified, simplified challenger model.

8. Level 3 fair value exposures review: for banks with material level 3 exposures, a thorough revaluation of the most important exposures was carried out on a selective basis - i.e. not all banks were analysed. For banks with material level 3 exposure, a revaluation of the most important securities was carried out. For the banks with material trading books, a qualitative review of trading book core processes (model validation, credit valuation adjustment, other fair value adjustments, independent price verification, P&L analysis and new product approval) was carried out, combined with a review of the most important derivative pricing models which price level 3 exposures (measured based on metrics such as level 3 gross mark-to-market). Additionally, a CVA challenger model was used to assess the banks' CVA calculation in detail.

9. Determination of AQR-adjusted CET1 ratio for use in ECB stress test and definition of remediation activities for banks following the comprehensive assessment: in order to correctly account for all AQR adjustments, an "AQR-adjusted CET1 ratio" was calculated for each bank. This AQR-adjusted CET1 ratio was calculated according to the Single Rulebook, fully reflecting Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) / Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) |38| rules (and taking into account the initial transitional arrangements decided by individual jurisdictions), and was checked in detail by each NCA.

Netting rules applied in the AQR

The results of the AQR work blocks are not additive i.e. the sum of the results of each work block do not add to the total outcome. When comparing individually assessed AQR-provisions from the credit file review and the projection of findings, and collectively assessed AQR-provisions from the collective provisioning assessment with the provisions recognised by participating banks, each portfolio was assessed on its own merit. This means that no netting between under- and over-provisioned portfolios was conducted. Furthermore it was determined that total provisions could not be reduced as a result of the AQR, and netting would occur within a portfolio only to a minimum of zero. Both of these rules reflect the prudential nature of the AQR methodology and introduce conservatism when assessing appropriate provisioning levels.

Additional details on how the credit file review was performed The credit file review (CFR) was designed to determine if exposures were performing or non-performing and to set the correct provisioning level for non-performing exposures.

In the AQR, this was performed on a large number of selected credit files of a bank's portfolio, using a risk-based sampling process. (This meant that those files that were either non-performing, large in exposure or considered at risk were selected in much greater quantity than smaller or less risky exposures). In total, the credit file review was performed on more than 119,000 loan files.

The credit file review was performed by NCA staff and/or independent audit firms, the so-called NCA bank teams. Members of these teams were only allowed to undertake the review if they were not the regular day-to-day supervisor or statutory auditor of the bank.

The CFR consisted of three components: data preparation, classification review and review of individual provisioning.

The data preparation involved collecting and verifying the information for the credit file review. Information was gathered by the bank and then provided to the NCA bank team in a standardised template. In total, banks provided more than 6 million data items in template form.

As a next step, banks provided the documentation on all selected debtors. In some cases this included hundreds of pages of loan documentation, providing information on the loan terms and characteristics, the credit memos, the business rationale behind extending the credit, the utilisation history of the facility, historical financials for the debtor, latest updates and appraisals on the borrower / the pledged collateral, information on eventual external guarantors and the latest covenants tests if applicable.

The work for the NCA bank teams then began in earnest with the performance of the classification review. A key component of this was to determine whether the exposure was performing or not. The documentation and recent information on the debtor were analysed for impairment triggers such as missed payments, evidence of bankruptcy or financial difficulty.

If a trigger was present, the teams checked whether a disruption of cash flow to the bank was to be expected or if the debtor would be able to honour all obligations to the bank on time. Debtors with expected impact on cash flow were (re)classified to NPE. Central benchmarking of impairment triggers and reclassification treatment led to equal treatment across banks and countries.

In total, the credit file review led to €81.3 billion of new NPEs across participating banks (post-projection) On all NPEs for corporate debtors, i.e. existing and reclassified, a review was performed to decide whether the provision that the bank holds against the exposure is appropriate. The review followed a present value of cash flows approach. The NCA bank teams first needed to decide if provisioning should be based on a "going concern" approach (i.e. the entity will continue to generate cash flows) or a "gone concern" approach (i.e. the assets of the company will need to be liquidated). Provisioning levels were then set based on the difference between the present value of cash flows and the exposure amount. This included the updated collateral valuations performed in the AQR. Again, the strict and prescriptive methodology and central benchmarking of provisioning levels led to equal and comparable results across banks and countries.

Portfolio selection for the review of provisioning levels

The ECB followed a risk-based selection approach in order to determine the portfolios that would be reviewed in the AQR. Out of the 130 banks participating in the exercise, 15 required special treatment as described later in this section ("Special cases"). In total, more than 1,300 portfolios were selected through the process described below which, after grouping and adjustments, resulted in 818 portfolios in the scope of the exercise.

Data gathering and portfolio definition

As a first step, a consistent data set covering all assets of each participating bank was gathered including standardised default data and other contextual information such as average risk weighting, coverage ratios by time in default and recent supervisory assessments. A data set of similar structure was gathered for level 3 fair value exposures. Based on these, assets were split into portfolios which were defined using a specific AQR approach to provide consistency.

Risk-based selection approach

The portfolios were selected for detailed analysis following a risk-based approach, the aim being to cover those portfolios with the highest chance of material misstatements compared to available capital. Therefore the results of the exercise cannot be extrapolated to unsampled portfolios. This involved the consideration by the respective NCA and the ECB of asset type, collateral coverage, supervisory history and current provision coverage, among other factors. For each bank, at least 50% of credit RWA and "half of the material portfolios" were selected. This led to larger and more complex banks having slightly lower proportions of credit RWA selected, but overall higher numbers of portfolios selected.

Figure 6 Illustration of risk-based portfolio selection, credit RWA coverage

Click to enlargeFigure 7 Illustration of risk-based portfolio selection, number of portfolios

Click to enlargeSpecial cases

Of the 130 participating banks, 15 cases required special treatment falling into three categories.

- Institutions with no banking credit risk: these institutions were only subject to the policy, processes and accounting (PP&A) review and, in two cases, the level 3 revaluation of non-derivative assets and derivative pricing model review. The 7 institutions which fell into this group are:

- RCB Bank Ltd

- Banque Centrale de Compensation

- C.R.H. - Caisse de Refinancement de l'Habitat

- Clearstream Banking

- RBC Investor Services Bank (performed non-derivative revaluation)

- UBS (Luxembourg)

- NWB Bank (performed non-derivative revaluation)

- Institutions with minimal banking credit risk: these institutions were exempt from the 50% of credit RWA and "half of material portfolios" selection criteria. The full AQR methodology was nonetheless applicable, but only for those items with credit risk. The 5 institutions in this group were:

- The Bank of New York Mellon

- Landwirtschaftliche Rentenbank

- State Street Bank Luxembourg

- Deutsche Bank (Malta)

- BNG Bank

- Institutions with very large intra-group exposure: institutions falling into this category were still subject to the two portfolio selection criteria, however in these cases the credit RWA coverage percentage was allowed to be calculated on a base RWA figure excluding the intra-group exposures. If this calculation approach was taken, intra-group exposures were not allowed to be selected as a portfolio. The 3 banks with high intra-group exposure were:

- Nordea Bank Finland

- Merrill Lynch International Bank

- RBS NV

Representativeness

Apart from a sufficient share of credit RWA of each bank, the selection approach aimed to cover a representative share of the entire universe of exposures. To that end, a significant share of credit RWA of all AQR asset classes was selected.

Figure 8 Selected exposures by asset class

Click to enlargeWhere particular asset classes or geographies were assessed to hold more risks, higher selection coverage was targeted e.g. the shipping sector. In addition, the portfolio selection covered more than 50 geographies inside and outside of the SSM.

Figure 9 Selected exposures by debtor geography

Click to enlargePortfolio selection for the fair value exposures review

The method for the selection of banks included in the AQR fair value exposures review was designed to focus the exercise on the most risky portfolios on banks' balance sheets, where the AQR adjustments of fair values could have a material impact on the CET 1 ratio.

For banks with material level 3 exposures, a revaluation of the most significant positions was performed (for many banks this was a single banking book portfolio held under the fair value option). For banks with the most important trading books, an AQR review of the trading book was conducted, consisting of a qualitative review of core trading book processes, and a quantitative review of the most important derivative pricing models. |39|

All 130 participating banks involved in the AQR were also in-scope for the CVA challenger model review outlined in Section 6.2.3.2.

Details of participating banks for each section of the review can be found in the Appendix.

3.2.2 STRESS TEST METHODOLOGY

The stress test exercise focused on projecting the solvency ratio (CET1 ratio) of the participating banks under two macroeconomic scenarios, namely a baseline scenario and an adverse scenario (see Section 3.2.3). The stress test covered a horizon of three years from 2014 to 2016.

The capital threshold for the ECB stress test exercise is defined in terms of Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) in accordance with CRR/CRD IV capital definition including transitional arrangements during the time horizon of the stress test (i.e. as per December 2013, December 2014, December 2015 and December 2016). |40| The minimum capital threshold for the baseline scenario is a CET1 ratio of 8%, thereby in line with the minimum capital threshold for the ECB AQR. The minimum capital threshold for the adverse scenario is a CET1 ratio of 5.5%.

The stress test exercise was performed under a static balance sheet assumption with the objective of achieving simplicity as well as cross-bank consistency and comparability. This implies a zero growth rate assumption for the balance sheet and the constant maturity profile of the bank's assets and liabilities over the horizon of the stress test confirmed by replacing maturing instruments with similar financial instruments in terms of type, credit quality and maturity. Exceptions to the static balance sheet assumptions were generally granted to the banks with restructuring plans.

Both the banking book and the trading book (including off-balance sheet items), as well as income and expenses, were subject to stress. The following risk dimensions were covered by the ECB stress test exercise. |41|

- Credit risk covered all counterparties (e.g. sovereigns, institutions, corporates and households) and all positions exposed to risks stemming from counterparty default (e.g. loans and securities). Credit risk was assessed through the impact of the macro-economic scenarios on default and loss parameters (probability of default and loss given default) thereby affecting both the profit and loss (P&L) account and RWA.

- Market risk covered all positions exposed to risks stemming from the changes of market prices, including counterparty credit risk. Market risk was to be assessed by applying a common set of stressed market parameters to positions held-for-trading, available-for-sale and positions at fair value through the Profit & Loss account, including sovereign positions in these accounting categories.

- Cost of funding and interest income affected all interest bearing assets and liabilities. The projected interest rates reflected re-pricing effects for new business (i.e. positions that replace the maturing positions) and changes in the reference rates for the floating rate items. Banks reflected the changes in their domestic sovereign bond spreads in the funding costs and pass on increased funding costs to customers. However, the pass-through was subject to certain constraints as banks were required to assume an asymmetrical pass through of interest rate changes on the asset and liability side respecting the caps and floors described in paragraphs 172 and 173 of the EBA methodology.

- Sovereign risk positions were treated depending on the exposure and accounting category. Sovereign exposures held at amortised cost (i.e. from the regulatory banking book) were stressed through PDs and LGDs based on rating notch downgrades provided by the ECB and ESRB. Sovereign exposures held at fair value were subject to the market risk parameters and haircuts (only for direct exposures i.e. exposures arising from immediate borrower basis) provided by the ECB and ESRB. The methodology prescribes a gradual phasing-out of prudential filters for all exposures (including sovereign) held as available-for-sale (AFS) in accordance with "minimum" transitional requirements set out in the CRR. Specifically, with respect to the preferential treatment of sovereign debt, 20% of the unrealised losses on assets in the AFS portfolio will not be filtered out in 2014, 40% in 2015 and 60% in 2016.

- Securitisation risk positions were stressed depending on the accounting treatment of a specific position. Risk weighted assets on all securitisations were subject to the increase in risk weights reflecting severe rating downgrades and based on three risk buckets: low, medium and high risk. Banks were asked to project impairments on exposures held at amortised cost. Exposures held at fair value were marked down in line with the market risk approach.

- Non-interest income and expense paths were projected using internal models, subject to the constraints set out in the EBA methodology, which are generally related to the recent historical evolution of this income type (2013 levels were used as a floor).

The stress test was performed by the banks in a constrained bottom-up fashion, under the macroeconomic scenarios and stress test methodology prescribed by the EBA in cooperation with the ECB.

Besides the static balance sheet assumption, the EBA methodology prescribed approaches to securitisations and sovereign risk, as well as a series of caps and floors on net trading income, net interest income and RWA.

In order to monitor the adequate application of the prescribed stress test methodology and scenarios, a quality assurance process was implemented following the submission of the stress test results by the banks. A review of the banks' bottom-up stress test results was performed on a stand-alone basis by the ECB quality assurance team in cooperation with NCAs. Further details on the ECB quality assurance process concerning the ECB comprehensive assessment results can be found in Chapter 4.

The join-up of the stress test and AQR results

Given that banks' stress test credit risk projections are driven by historical experience of default and impairment flows, AQR findings that relate to observed default and impairment flows should have an impact on forward-looking projections. For instance, if a bank estimated a PD for a portfolio of 1%, but the AQR showed it had underestimated the amount of defaults it experienced during 2013, then the real PD it should have applied may be higher than the 1% estimated by the bank.

Furthermore, AQR findings relating to the fair value of assets also have a bearing on future projections. For instance, if a bank incorrectly values a bond, it will also incorrectly stress the valuation of the bond (given the underlying valuation model is incorrect).

Finally, a series of other AQR-related findings have a direct bearing on the appropriateness of bank's stress test projections. For instance, in the AQR, NCA bank teams set an "auditor allowable amount" for deferred tax assets (DTAs) reliant on future profitability based on the income generating capacity of the bank and the local tax law. |42| In some cases, banks breached this amount when projecting DTA formation in the stress test results.

To address these issues, AQR findings were used to adjust each bank's relevant projections (e.g. PD and LGD parameters) so that relevant line items in the stress test fully reflected the findings from the AQR - this process was termed the "join-up". In particular, this allowed for the following effects to be adjusted for on a granular basis.

- Underestimation of PDs due to NPE misclassification identified in the AQR.

- Underestimation of LGD due to coverage ratio changes in the AQR.

- Double counting of losses that the bank classed as future losses but were included as incurred losses in the AQR.

- Fair value (including AFS) assets' valuations inappropriately stressed due to inappropriate valuation models used.

- DTA formation over the stress test exceeding the auditor allowable amount.

- Inappropriate application of tax rates, out of line with EBA methodology.

The join-up of AQR and stress test results was carried out in accordance with the comprehensive assessment stress test methodology, published by the ECB on 8 August 2014. |43| The work was conducted following the completion of the stress test. The process of joining the AQR and stress test outcomes involved centrally-led calculations (both by the ECB and the NCAs).

3.2.3 THE BASELINE AND ADVERSE SCENARIOS

The stress test exercise consisted of two macroeconomic scenarios, namely a baseline scenario and an adverse scenario. The baseline scenario was provided by the European Commission. The adverse scenario for the stress test was proposed by the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) in close collaboration with NCAs, the ECB and the EBA, and finally approved by the EBA Board of Supervisors.

The baseline scenario was based on the European Commission winter forecast, extended to cover the third year of the stress test (i.e. 2016), and was meant to reflect the most plausible scenario. |44|

The adverse scenario captured the prevailing view of current risks facing the financial system in the EU, as identified by the ESRB. It provides forward-looking paths for key macroeconomic and financial variables for all EU countries and a large number of non-EU countries, expressed in deviations from the baseline. The adverse scenario was designed to reflect the systemic risks that were assessed as representing the most pertinent threats to the stability of the EU banking sector: (i) an increase in global bond yields amplified by an abrupt reversal in market participants' risk perception, especially towards emerging market economies; (ii) a further deterioration of credit quality in countries with weak demand; (iii) stalling policy reforms jeopardising confidence in the sustainability of public finances; and (iv) the lack of necessary bank balance sheet repair to maintain affordable market funding. |45|

On average in the euro area, the adverse scenario leads to deviation of euro area GDP from its baseline level by -1.9% in 2014, -5.1% in 2015, and -6.6% in 2016. The euro area unemployment is higher than its baseline level, by 0.3 percentage points in 2014, by 1.2 percentage points in 2015, and by 2.2 percentage points in 2016. For most advanced non-euro area economies, including Japan, the UK and the US, the scenario results in a negative response of GDP ranging between 5% and 7% in cumulative terms compared to the baseline.

Furthermore, while the adverse scenario does not strictly embody a prolonged deflationary environment, it does entail material downward pressures on inflation. Thus, the scenario leads to annual inflation rates for the euro area below the baseline rates by 0.1 percentage points in 2014, by 0.6 percentage points in 2015, and by 1.3 percentage points in 2016. The implied adverse inflation rates amount to 1.0% in 2014, 0.6% in 2015 and 0.3% in 2016.

In comparison with past EBA and CEBS |46| EU-wide stress test exercises, the scenario for the 2014 EBA exercise was more severe, e.g. in terms of impact on GDP compared to the baseline. For instance, the difference between adverse and baseline GDP growth rates was around 5.1 percentage points at the end of the second year of the 2014 stress test exercise compared to between 3 and 4 percentage points in the previous three EU-wide exercises (see Figure 10). Also, as mentioned, in the current stress test there is a third year that contributed to the rigour of the exercise.

Figure 10 GDP impact across CEBS/EBA EU-wide stress test exercises in the euro area, deviation between adverse and baseline

Click to enlargeMoreover, in terms of overall severity, the magnitude of the cumulative shocks in the EBA stress-test exercise is broadly in line with those of the 2014 USA Federal Reserve's CCAR |47| adverse scenarios. Overall, in terms of peak level deviations from baseline GDP, the EBA stress test adverse scenario lies roughly in between the CCAR "adverse" scenario and the CCAR "severely adverse" scenario. Thus, over the nine-quarter horizon of the 2014 CCAR, the cumulated deviation from baseline GDP level reaches a maximum of 5.2% under the "adverse" scenario and a maximum of 8.9% under the "severely adverse" scenario. In the EU exercise, the maximum deviation of EU aggregate GDP from baseline over the 12 quarters amounts to 7.0%. Furthermore, when comparing the CCAR scenarios with the adverse scenario of the EBA 2014 stress test it has to be remembered that the starting points and the baseline scenarios differ in that they are generally substantially weaker in the euro area compared to the US.

3.3 RISKS NOT ADDRESSED IN THE COMPREHENSIVE ASSESSMENT

In broad terms, the carrying value of all assets was within the scope of the AQR, along with the calculation of the solvency ratio but with the exclusion of the calculation of risk weighted assets. Specifically, some further exposures were excluded from the review for various reasons.